Two young men lay flat on the pavement, faces up, feet pointed at the other, motionless.

A wild shootout had just ended at noon on a Sunday outside the courtyard of an apartment complex on Chef Menteur Highway in New Orleans East, with no victor.

Justin Ganier was lined up in a parking stall, sneakers propped against a yellow curb, dead at age 23. Robert Moody, 25, wasn’t far behind, shot 17 times and bleeding through his clothes in a scene posted to Instagram.

The sudden, violent deaths of two young Black men settled a dispute that began the previous evening and escalated that morning — an eruption over baked treats, witnesses told police. Moody lived there with his girlfriend, who had invited a friend, Ganier and the couple’s young boy to stay.

New Orleans police investigate a shooting at the Gentilly Ridge Apartments in the 6000 block of Chef Menteur Highway that killed two men Sunday, Jan. 16, 2022. (Staff photo by Scott Threlkeld, NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate)

“They cooked my son’s cinnamon rolls,” said Moody’s mother, Christy Dorsey, recalling a homicide detective’s account. “My son went off about the cinnamon rolls. ‘Why you cookin’ my stuff?’ So my son cooked the girl’s cookies. The cookies got burnt. So the girl told my son, ‘You must can’t read.’ ”

Moody had a stutter, and that kind of wisecrack would get to him, said his stepfather, Eddie Tillman. Witnesses told police he threatened to kill the woman. Moody and his girlfriend left for Walmart. “The girlfriend said she tried to defuse it,” Tillman said.

When they returned from the store, Ganier, who had been at work, was there with his mother, packing up. The two men traded words before the gunfight.

One witness described it as “like 'The Matrix,' ” as both men fired from feet away while rolling on the ground. Police deemed Moody the perpetrator and first to fire, counted it as one murder and cleared two homicides as solved.

To Tillman, the deadly shootout a year ago seemed to epitomize a familiar escalation among armed young Black men in New Orleans, a deadly game of chicken that he said he urged his stepson to avoid by stashing his gun.

“It’s like you won’t back down,” he said. “You got two people carrying guns for protection, so you’re not scared to use it. So he knows he’s strapped, and he knows he’s strapped. It’s a thing of, 'You gonna use it or not?' ”

Murder capital

Police lights illuminates the 1800 block of South Rampart street as the New Orleans Police Department investigates the scene where a car drove by and shot outside a repast for 18-year-old Rickey Smith who was shot and killed Jan. 18 in Central City, in New Orleans, Friday, Jan. 27, 2023. An 18-year-old victim received a graze wound to his ankle about 6 blocks from where Rickey Smith was killed. (Photo by Sophia Germer, NOLA.com, The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate)

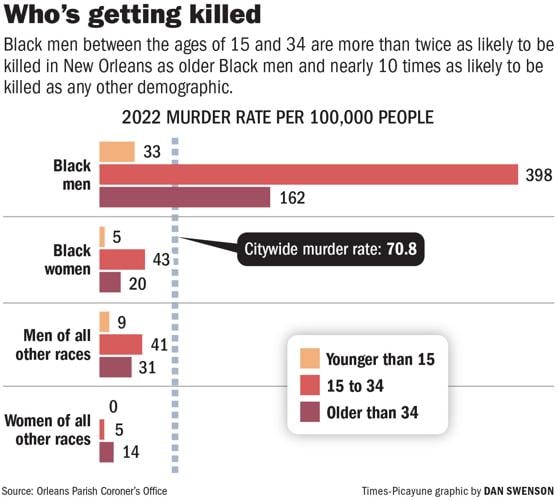

In the nation’s most murderous city, young Black males are getting killed at rates reserved in most other places for diseases affecting the elderly.

Close to half of New Orleans’ 265 murder victims last year were Black males ages 15 to 34, police data shows. Over the past three years, 1% of that cohort was murdered in the city. At that rate, 1 in 14 Black youths in New Orleans will be slain before they reach 35.

The murder rate for that group was nine times higher than for everyone else in New Orleans last year. It was higher than the rate at which local seniors die from strokes, the third leading cause of death for New Orleanians 65 and over, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data shows.

New Orleans police data on murder suspects suggests that a similar, slightly younger cohort of Black males is doing the bulk of the killing.

The grim numbers add up to what many view as a ballooning public health crisis, a contagion of deadly violence that has gripped New Orleans over three straight years, with an outsized toll on young Black males.

If there’s an effective treatment, researchers and advocates say, it must target a culture in which shooting has become a go-to response to seemingly any threat.

New Orleans appears to lead a national trend. Homicides of juveniles rose sharply in 2020, to their highest numbers since 2006, while homicides committed by juveniles also rose, according to the most recent federal data. In New Orleans, 24 juveniles were slain last year, up from 17 in 2021.

Lines between perpetrator and victim easily blur in a city where gun violence is normalized among youths and trauma informs every encounter, said Samantha Francois, executive director of the Violence Prevention Institute at Tulane University.

“Most of the perpetrators of violence we do know were previously victims of violence. They may not have been a shooting victim, but they have a history or a past of other forms of violence victimization,” she said.

Francois said the institute’s work with New Orleans youths reflects a population “kind of left to fend and deal on their own,” with little organized around their interests.

“We’re talking about young people with diagnosed and diagnosable mental health concerns and psychological disorders, to those just struggling to deal,” she said.

“And what we see as a result of that fending and dealing is, ‘Let me pick up a gun so I can protect myself.’ Or, ‘Let me pick up a gun so that I’m not a victim.' I want to avoid even being in that group of victims, so I’ve now become the aggressor.”

‘Feedback loop’ of violence

The NOPD investigates a homicide near the Blue Plate Lofts in the 4700 of Thalia St. near Jeff Davis Parkway in New Orleans Wednesday, Nov. 11, 2020. (Photo by David Grunfeld, NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate)

Nearly all young Black males who are murdered in New Orleans were shot, and the frequency of shootings in that population is increasing sharply, state trauma data shows.

At current rates, Black males who live in New Orleans from ages 15 to 24 have about a 1 in 8 chance of showing up shot at University Medical Center over that perilous decade of life.

Social media, where threats and violence are broadcast in an instant, has “compressed the feedback loop” for violence among youths, Francois said.

“It’s developing into a belief that, ‘This is an acceptable thing in my community, in the people I identify with. This is an acceptable way of dealing with challenging stuff in my life or when I feel like I might be challenged,' ” she said.

Tulane’s researchers are only beginning to probe police records and hospital data to understand deeper trends in the surge in shootings and killings in New Orleans, and the extent to which juvenile offenders drive it, the institute’s directors said.

Two years ago, the institute launched one of five national research hubs funded by the CDC to study youth gun violence, after decades in which Congress barred such funding under pressure from gun rights groups.

Every morning, the institute receives a list of gunshot trauma patients at UMC, as part of an intervention program that began in August for young shooting victims. Anecdotally, those encounters point to personal disputes more than organized violence, said Julia Fleckman, associate director of the institute.

“A lot are domestic incidents between relatives or friends,” she said. “It’s not necessarily related to them being affiliated with a gang or having some kind of connection to illegal activity.”

‘Culture of fear’

Christy Dorsey stands in the former bedroom of her son Robert "Beedy" Lee Moody Jr., as his urn is illuminated on the wall in New Orleans, Sunday, Jan. 29, 2023. Beedy was shot multiple times and killed during a shooting in New Orleans East on Jan. 16, 2022. (Photo by Sophia Germer, NOLA.com, The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate)

For decades, gun violence has been “persistent as the leading cause of death and disability among this population,” said Joseph B. Richardson, a University of Maryland professor of African American studies and medical anthropology.

But resources for intervention have been slow to materialize, especially in the South, he said.

“We’ve just totally dropped the ball in addressing it in the same way we’ve addressed opioid addiction,” he said. “I don’t see a similar level of sensitivity and compassion for this racial group.”

Richardson views the pandemic as an isolating catalyst on top of a “culture of fear” that young Black males experience in violent neighborhoods.

“We make assumptions people are carrying guns because they intend to maliciously harm someone. Many people carry guns because police aren’t going to respond to your safety needs,” he said. “This is kind of the American narrative: You have to protect yourself.”

At St. Anna’s Episcopal Church, which displays a running list of area murder victims outside the rectory on Esplanade Avenue, the Rev. William Terry points to “these disasters of poverty and systemic racism. That’s an epidemic. That’s like the underlying virus that’s always there and becomes very aggressive during times of social stress.”

Terry, however, sees a difference from the hard days after Hurricane Katrina, when displaced residents seemed to yearn to socialize.

“After the pandemic, it seems like a big apprehension to reconnect. It’s like they lost their social skills,” he said. “A generation of kids spent two years of their life trying to be educated using video. It really wasn’t that successful.”

Beyond the isolation of COVID restrictions, Tulane sociologist Andrea Boyles pointed to long-standing metrics in education and access to health care that place Louisiana near the bottom of national rankings.

A memorial, neighbors said has been there for a number of years, leans against a post, as the New Orleans Police Department investigates the scene of a homicide 2 blocks away in the 5300 block of Marais Street in the Lower 9th Ward neighborhood of New Orleans, Wednesday, Jan. 25, 2023. (Photo by Sophia Germer, NOLA.com, The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate)

“We live in an environment where people have more access to guns than they do social and human services,” Boyles said. “When that is the case, and remains the case, then we can anticipate crime at times to fluctuate.”

A study by LSU researchers looking at crime in New Orleans before and after Katrina found homicides, assaults and robberies were concentrated in disadvantaged areas, but they were less common in areas where residents trusted their neighbors.

COVID and displacement from Hurricane Ida may have had a disasterlike effect, said Michael Barton, an LSU sociology professor who co-wrote the study.

Barton also pointed to areas of the city that “never really built back” after Katrina.

“There’s still a lot of disadvantage in a lot of places where things can occur outside of the purview of police,” he said.

Dispute turns deadly

Christy Dorsey and Eddie Tillman Sr. listen to a recording of a call refers to the day Robert "Beedy" Lee Moody Jr., was shot and killed in New Orleans East, in New Orleans, Sunday, Jan. 29, 2023. (Photo by Sophia Germer, NOLA.com, The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate)

Police arrived to find Ganier and Moody splayed out in the parking lot. It was enough for then-Police Superintendent Shaun Ferguson to send a text message to Mayor LaToya Cantrell a few hours later.

“I was just calling to give you this crazy gist from Chef,” it read.

If it was crazy, police didn’t find much of a whodunit. A brief incident report describes the two men as roommates, though relatives said they were hardly close.

Ganier’s mother, Candatha Beverly, said her son and other relatives were displaced in late 2021, when she moved from Tennessee Street in the Lower 9th Ward. Another son had been shot and paralyzed from the waist down, she said, and afterward, his rivals came to shoot up the house.

Beverly acknowledged that Ganier was active in gangs and street crime after dropping out of The Net Charter High School when he turned 18.

“I’m not going to say he was the best kid after that. Pretty much he was on his own, dealing with this Instagram social media, these gangs and everything,” she said. “He was into that pulling on (vehicle) door handles and everything. I tried to get help with him. They told me they couldn’t help him unless he was in the system.”

A note sticks to the altar which holds the urn of Robert "Beedy" Lee Moody Jr., in New Orleans, Sunday, Jan. 29, 2023. Beedy was shot multiple times and killed during a shootout in New Orleans East on Jan. 16. He was 25 year old. (Photo by Sophia Germer, NOLA.com, The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate)

Beverly said she rushed over when she got a call about an argument and violent threats at the apartment. When she arrived, her son was packing up to leave, but Moody was still fuming about Ganier's girlfriend.

“I guess he got highly upset because she used the cinnamon rolls. It escalated from there,” she said. “My son had to be the protector for his son and his girlfriend. She called and said (Moody) was talking about threatening her and the baby.“

The cinnamon rolls were for the child, who was hungry, Beverly said.

“Talking escalated to shots,” she said. “I ran for cover because I had my grandbaby. I seen them on the ground. I called 911. I told them my baby was on the ground, he was dead. He wasn’t moving.”

Moody, a mechanic, wasn’t into gangs or gunplay, Dorsey said as she sat last month a few feet from his urn.

“We call them studio gangsters,” she said. “Like they have studio rappers, who think they’re rappers because they’re at home.”

A piece of the wall in the old bedroom of Robert "Beedy" Lee Moody Jr., is cut out for his urn in New Orleans, Sunday, Jan. 29, 2023. Beedy was shot multiple times and killed during a shootout in New Orleans East on Jan. 16. He was 25 year old. (Photo by Sophia Germer, NOLA.com, The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate)

Still, one of her son’s prized possessions was a black extended drum clip that he’d bought online. Dorsey said it resembled a tuna can.

“These youngsters, they call it a ‘dick,’ ” Tillman said. “You’ll find a lot of them walking into the corner store with the clip sticking way out. They out with ’em. It’s just ridiculous.”

Moody crowed over his purchase and kept it close, attached to his handgun, though it wasn’t seen with him as he bled out in the parking lot, said Tillman.

A copy of Moody’s autopsy report, which Dorsey received this month, added to the couple’s doubt over just what happened. It showed her son was shot 17 times, front and back.

Dorsey suspects a third shooter jumped in and picked up one of the guns to kill her son, an account she said makes more sense than the one police gave her.

“This can’t be over no cinnamon rolls,” she said.

At the start of 2023, New Orleans was considered to have the highest murder rate of any large city in the country.