Why Walz’s proposal to use tax credits to make childcare more affordable is problematic

In Minnesota, families with incomes less than $55,300 can get back up to $1,050 in qualifying care expenses under the state’s Child and Dependent Care credit. Families with two or more children with the same income can get back up to $2,100. The credit is reduced to $600 for one kid and $1,200 for two or more kids for families with incomes over $55,300. The credit phases down to zero when incomes reach $79,300.

Governor Tim Walz wants to expand the credit. In his new budget proposal, if you are a family of four — with two children — and make under $200,000, you could receive $8,000 back for qualifying childcare expenses. If you are a family of five, with three children, you could get up to $10,500. Furthermore, Walz wants to introduce a child tax credit, whereby families making less than $50,000 will get back $1,000 per child, up to three children. Like the Child and Dependent Care Credit, the child tax credit also gradually phases with income. This will, supposedly, reduce (childcare) costs for Minnesota families.

This is not all that Walz is proposing to make childcare more affordable, however. In addition to spending over $2 billion on the two tax credits, Walz also wants to spend over a billion dollars to update CCAP reimbursement rates — which are some of the country’s lowest — as well as support the state’s childcare industry and workforce. Walz is also proposing increasing ‘investments’ in the basic sliding fee program, some more spending on Early learning scholarships as well as some funds to expand free Pre-K.

Public funding is no panacea

Certainly, the lack of access to affordable high quality childcare is a big issue in Minnesota. But as research from American Experiment has shown, increasing funding wouldn’t likely address the issue.

This is because public funding doesn’t address the root cause of the crisis — government overregulation. Instead, what public funding does is increase demand which then drives costs up, especially if supply remains unchanged or goes down.

Tax credits are problematic

But outside of the fact that public funding won’t address the childcare crisis, there are other issues specifically associated with Walz’s main proposal — tax credits — as a way to reduce childcare costs.

For one, low-income families use formal care at lower rates compared to their rich counterparts. So, despite its intent, expanding the child care and dependent tax credit wouldn’t help those most in need of affordable childcare — low-income families. It might push them entirely out of the market by raising prices. But expanding tax credits is also likely to wreak havoc on the state’s tax system and budget.

Low-income families won’t benefit

How do low-income parents pay for childcare?

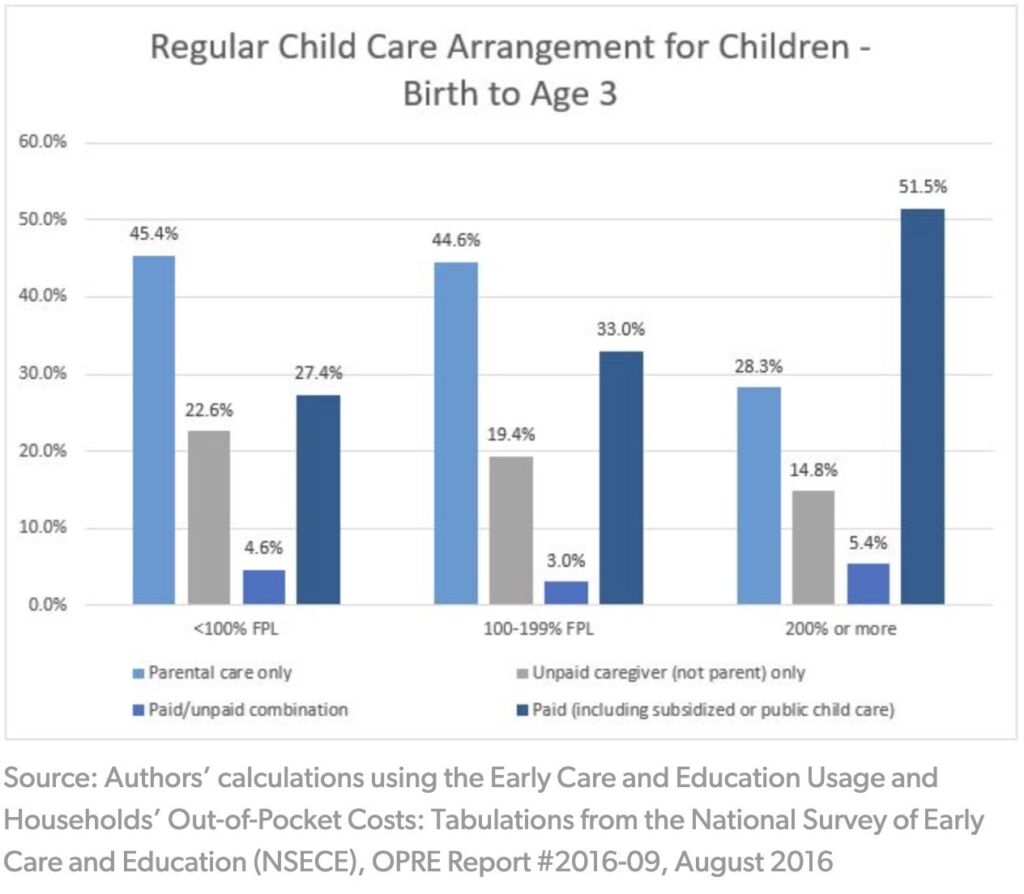

According to Angela Rachidi at the American Enterprise Insitute (AEI), low-income parents often don’t pay for childcare. This is because they mostly utilize what is termed Family Friends and Neighbor (FFN) care. In a 2016 study, Rachidi estimated that while over half of families earning 200 percent or more of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) utilized paid care for kids under 3, only 27 percent of those under the FPL did. And for those between 100 and 200 percent of the FPL, the proportion was just 33 out of every 100.

Low-income parents often utilize parental care at higher rates than higher-income parents, the latter preferring formal care instead. To some extent, this is due to affordability. But it is also about preferences.

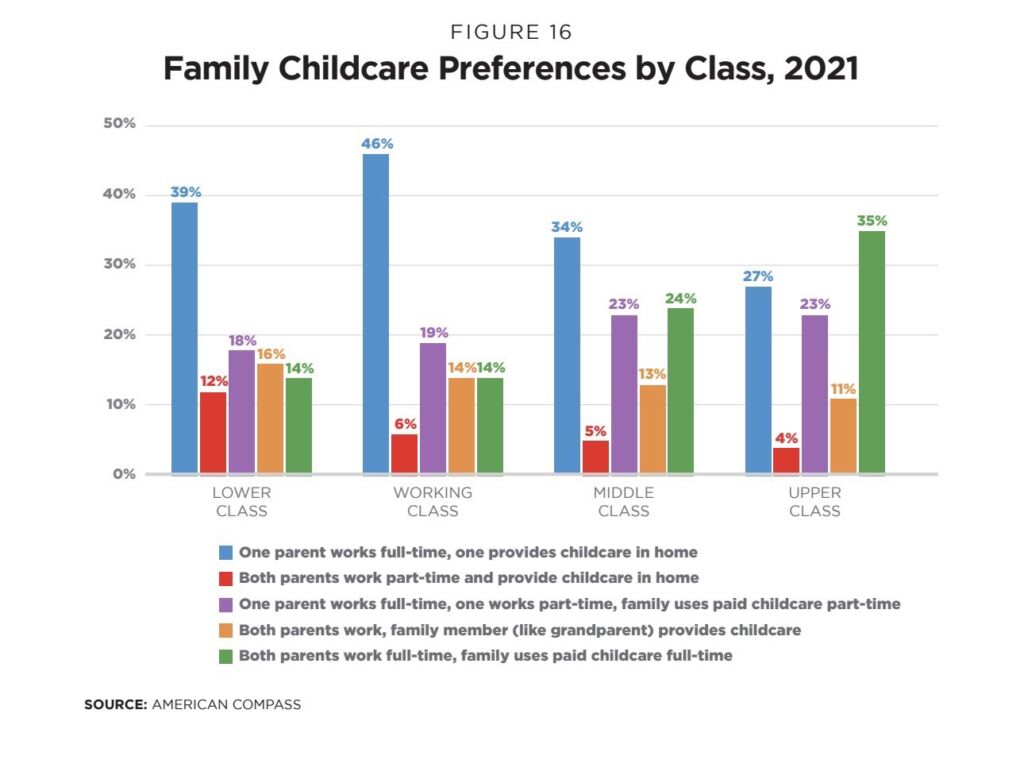

In their 2021 Home Building Survey, American Compass found that lower-class families — those with less than a college degree and with incomes less than $30,000 — and Working class families — those with no college degree and with incomes below $70,000 — show a higher preference for parental care than another type of care. Asked about their preferred care arrangements, low-class and working-class families would rather one parent stay at home and provide care. Only less than 20 percent of each preferred an arrangement where both parents worked and children received formal paid care.

In contrast, middle and upper-class families prefer formal paid care to other types of care arrangements. One possible explanation for this preference gap is potentially the fact that most poor mothers work nonstandard schedules, which calls fall for flexible care — something that formal paid care cannot accommodate. But all in all, poorer families simply have lower demand for formal childcare.

And even when asked about what kind of government assistance they would prefer, low-income parents preferred direct cash over other mechanisms of subsiding care like paid family leave or subsidies — mechanisms that middle and upper-class as well as working families preferred.

Certainly, refundable tax credits can work like cash assistance. But tax refunds are only received once a year. Moreover, families have to spend money on childcare — for something like childcare and dependent tax credit — to get their money back. And to get the child tax credit refund, families have to earn income.

But low-income families have no money to spend on childcare, to begin with, and they are also unlikely to be in the labor force. For that reason, they are likely to prefer monthly checks to tax credits.

Other issues with tax credits

Tax credits are also an expense for the state government. If Governor Walz’s budget proposal passes, the state will not only be getting less revenue than before — on the account of the numerous families whose tax liabilities will be scrapped off when these credits are applied — but the state will also have to find the money for the refunds. This will potentially present some problems to Minnesota’s ever-growing budget.

According to the Minnesota Department of Revenue, 25 percent of all adult Minnesota taxpayers paid zero income tax in 2018. Walz’s expansion of tax credits grows that proportion significantly, forcing our state to rely even more heavily on the state’s rich to fund our expanding government. But with more and more of Minnesota’s rich moving from the state, it’s even more likely that we are headed for a future where tax revenues would not be able to cover all of our government’s spending obligations.

Not to mention, tax credits also carve out complexities in the tax system that need not be there. While they do reduce the tax burden for some taxpayers, they do so in a distortionary way. They are a way of redistributing income from high-income taxpayers to low-income taxpayers, and not an efficient way to cut taxes, unlike uniform rate cuts across the board.

The consequences

Spending money on childcare — in any way — won’t solve any issue. It will only drive prices through the roof by increasing demand.

But making childcare affordable using tax credits is an especially ineffective way to help poor families — who need help the most — afford childcare. Poor families are usually not part of the childcare market and instead use and prefer unpaid care.

Knowing these problems with tax credits, others have proposed universal childcare instead. Universal childcare, however, also does not deal with the root cause of the crisis. And in addition, it is associated with a myriad of other unintended consequences, like negative outcomes among children who use such programs.

To say the least, there is no magic wand to resolve the childcare crisis. But with tax credits, Governor Walz. will only sideline those who need help the most — poor families — and raise childcare prices for everyone all the while will also making the tax code much more complex and putting Minnesota at risk of future fiscal imbalances.