The Texas landscape doesn’t get more fantastical than Caddo Lake, a nearly 27,000–acre swamp on the Texas-Louisiana border, thought to have formed around 1800 after centuries of fallen-log pileups. Spanish moss dangles from bald cypress trees, whose roots protrude like termite mounds above the water. Though just nine feet in average depth, the lake teems with all manner of creatures, including alligators, snakes, and paddlefish, which predate the dinosaurs by 50 million years. Some even claim to have seen Bigfoot wandering around.

“It’s kind of wondrous,” says artist Billy Hassell. “It looks primeval and mysterious, and you can definitely get lost in there.”

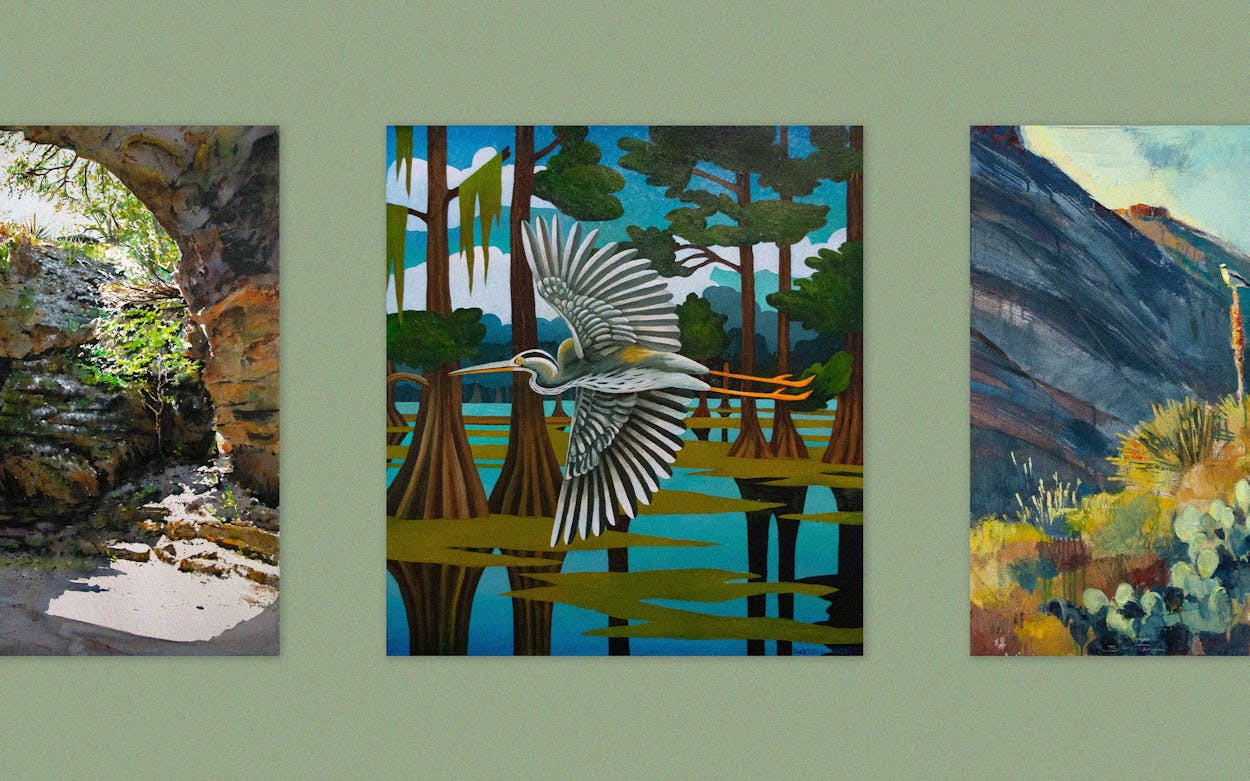

Hassell grew up in Dallas and first glimpsed the wild through the taxidermy dioramas at the Museum of Natural History; now he takes sketching trips to places like Caddo Lake State Park, a 484-acre gateway to the larger wetland. On a trek there three summers ago, he saw a great blue heron, which sports a six-foot wingspan, lift from its fishing perch and soar past his airboat. Days later in his Fort Worth studio, he set about illustrating the encounter. The finished oil painting, a three-foot-wide canvas, freezes the waterfowl in stylized flight, its wings outstretched like an ancient Egyptian bird god.

Hassell’s piece is the striking opener of the new exhibit “Art of Texas State Parks” at the Bullock Museum in Austin. The show celebrates the hundredth birthday of Texas State Parks through 34 paintings commissioned for the occasion by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. It’s meant to spur appreciation for the beauty and diversity of the state’s public land. But for artists like Hassell, nothing beats actually getting out there in person—preferably with a paintbrush in hand.

“It’s more than just gathering source material,” Hassell says. “Sitting and looking and watercoloring really enables me to process the experience in a deeper way. It sticks with me longer.”

Artists owe their ability to sketch in Texas state parks to former governor Pat Neff, who established the system in 1923. Neff was peeved that Texas had given away or sold “practically all of her public lands” since joining the Union in 1845. He recognized a need for picturesque spots where “rank-and-file” citizens could escape in their new Model T’s to “forget the anxieties, the strife, and vexations of life’s daily business grind.” His five-member State Parks Board zigzagged thousands of miles up and down the state in search of future park locales. “Wherever wood grows and water runs is a good state park site,” Neff said.

Today, the state parks system includes 89 parks, natural areas, and historic sites that span more than 640,000 acres (a land mass roughly equivalent to Rhode Island) and draw nearly 10 million visitors each year. Yet unlike the National Park Service, which has promoted art in national parks through art competitions since 1986 and artist residencies since 2006, “there’s never been an officially sanctioned group of artists to go in [to the Texas parks system] and do a visual overview,” says William Reaves, a former Houston gallerist and one of the Bullock show’s organizers.

The idea for such a survey came about after Reaves and his wife Linda collaborated with Andrew Sansom, founding director of the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment, on a 2017 book, Of Texas Rivers and Texas Art. When that project ended and the state park system’s centennial approached, Sansom thought, “Why don’t we do this again, but bigger?”

The trio easily convinced the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department to sign on as a partner. Instead of pulling from the abundance of existing Texas landscape paintings, they chose to commission fresh imagery made specifically for the park system’s centennial by thirty well-established artists (the youngest was born in 1975), officially dubbed “State Parks Centennial Artists” by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission. Most work in the traditional styles of realism and impressionism, using mediums such as oils and watercolors, which sets the project’s more conservative tone. (The early twentieth-century painter Julian Onderdonk, sometimes called the “father of Texas painting,” would feel right at home here). After the artists received their marching orders, each visited at least two sites within the parks system. The resulting 65 artworks appear in The Art of Texas State Parks, A Centennial Celebration, 1923–2023, published by Texas A&M University Press. From the book, Bullock curator Angie Glasker selected the works that now grace the museum’s carpeted third-floor rotunda.

Some visitors might be disappointed to find that an exhibit titled “Art of Texas State Parks” excludes more contemporary art formats such as installation and video (which could have brought the sounds of the landscape to life). But overall, the show is bound to be a crowd-pleaser, taking visitors on a scenic tour of Texas’s seven geographic regions, from the Piney Woods to the South Texas Plains. In his acrylic painting “Ancestors,” San Antonio artist Clemente F. Guzman III juxtaposes two reptiles millions of years apart. A rose-bellied lizard rests in a dinosaur track at Government Canyon State Natural Area, looking as real as the fruit in a seventeenth century Dutch still-life painting (no wonder Guzman illustrated Texas Parks and Wildlife magazine for nearly three decades). Jim Malone’s “Bluebonnets and Blue Herons Visit Cleburne State Park” is more abstract. The mixed media piece feels kindred to a Joseph Cornell assemblage, evoking the feeling of the place through fragmented imagery—a map, a bird, the night sky. If it were a poem, it might be a haiku.

In contrast, David Caton’s dramatic oil painting, “To the East, Big Bend Ranch State Park,” could be an epic. Based in Utopia, Caton visits the park a few times each year, often steering his SUV up the “Big Hill” on State Highway 170 to catch a westward view of the Rio Grande snaking through the Colorado Canyon below. He’s painted the river “at least fifty times,” he says, explaining that water is a metaphor for what he wants to do with paint—“a little looser, a little thicker, a little freer.” But during a 2019 visit, Caton found himself drawn in the opposite direction, where the setting sun illuminated a bone-dry cliff face. It took about an hour to complete a small study—a meditative process as important as the final product. “I don’t want to get too metaphysical, but it’s often a transcendent experience when you’re out there and the sun is going down,” Caton says. “You’d have to be very cynical to not be emotionally overwhelmed by those experiences.”

It’s no surprise that the Big Bend region fueled some of the show’s most awe-inspiring work, with notable contributions from artists like William Montgomery and Margie Crisp. But perhaps my favorite piece is Mary Baxter’s oil painting “Butcherbird,” named for the Loggerhead Shrike, a songbird known among ranchers for its unseemly habit of impaling insects on barbed wire fences and such. “The first time you see it, you think, gosh, what kind of human could have been that sick?” Baxter says.

Baxter is a veritable cowgirl who first moved to West Texas 27 years ago to graze cattle. She fell in love with the rugged fragility of the Trans-Pecos landscape and began going out at sunrise to capture it on pine boards primed with old house paint. “I didn’t have a clue how to do plein-air,” she says. “But I kept thinking, ‘Wow, I really like how this landscape looks.’ ” She happened upon the shrike one morning in 2019, while camping out at Chinati Mountains State Natural Area, a nearly 39,000–acre reserve slated for new state parkdom. The bird stood atop a spiky sotol plant in a large canyon, its feathers gold-lit before the purple mountains beyond. It soon flew off, but Baxter stayed to sketch the scene. Later in her studio, she rendered it in juicy washes of color that give way to rich impasto.

But “Butcherbird” is more than just a pretty picture: its subject, the Loggerhead Shrike, is declining in Texas—likely due to the same human-induced changes behind the plummet in biodiversity worldwide. The bird’s presence in the painting reminds us that places like Chinati are delicate natural habitats that animals depend upon for their survival. “It’s their livelihood,” Baxter says. “Human recreation shouldn’t come at the expense of wildlife.” It shows how—as Texas’s population booms and climate change looms—art can not only celebrate the landscape, but also inspire critical questions about our relationship to it.

It’s a challenge for the next century of parkgoers, some of whom may be inspired by this stunning exhibit to get out in nature and experience the state’s park system as the show’s artists do—by making art.

- More About:

- Art