Few things satisfy Skip Gallagher like sanding wood.

The University of New Orleans chemistry instructor, Algiers Point activist and former Louisiana statehouse candidate would grab old shutters and baseboards discarded after Hurricane Katrina, toss them in his truck and set about working over the grain, hour upon tedious hour.

“You leave me alone with an old-growth piece of cypress or old pine … it’s gorgeous,” said Gallagher, 59. “I don’t know anyone who has spent more time sanding than me. It’s pretty sad.”

Lately, Gallagher has turned his embrace of mind-numbing tedium into a civic power tool, training it for more than a year on the New Orleans Police Department. The results have been scandalous.

The FBI is in the midst of a widening probe into alleged payroll fraud on the force, thanks to timesheets that Gallagher spent an estimated 1,600 hours gathering, compiling and analyzing. He says his research shows numerous officers double-dipping with on-duty shifts and off-duty security jobs, or logging implausible hours.

Police Superintendent Shaun Ferguson recently said 11 officers are in the federal crosshairs, with five having received FBI “target” letters. The Police Department, the New Orleans inspector general and the Office of Independent Police Monitor launched their own investigation into the timesheets of 33 officers, based on data from Gallagher's hand-built spreadsheets.

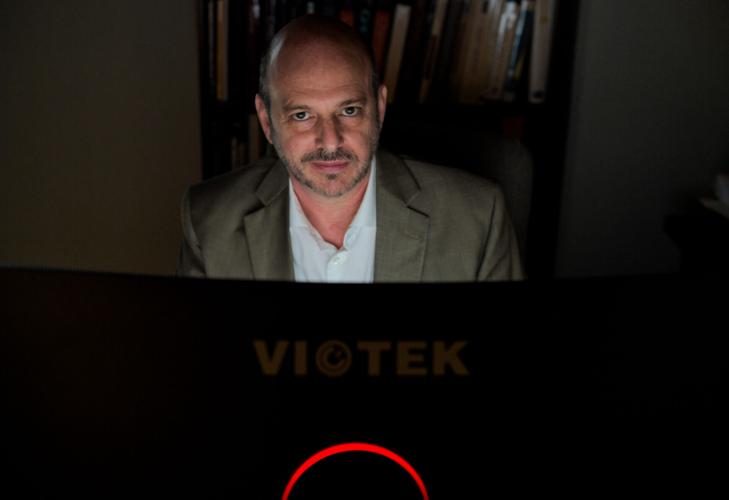

Skip Gallagher, a chemistry instructor, poses in office at the University of New Orleans on May 12, 2022. When not teaching, Gallagher spends his time scrutinizing public records, and his research has helped an FBI investigation into New Orleans officers who abuse special security details.

The officers under scrutiny could see criminal charges. An internal report on a police captain, Sabrina Richardson, has been referred to District Attorney Jason Williams’ office for possible charges.

The scandal has left egg on the faces of City Hall and Police Department officials as they reach the homestretch of federal oversight of the Police Department after a decade. Gallagher’s efforts exposed a police force that didn’t – and now says that it couldn’t – track compliance with officer work limits. City Hall has pledged several reforms.

The Office of Police Secondary Employment, set up in 2013 to regulate the off-duty work, said last fall that it audited officers’ hours regularly and saw “no concerns” about officers logging improper hours. But Gallagher’s spreadsheets suggest otherwise.

“It’s their job. They should be investigating it, and they’re not,” Gallagher said. “It’s not fun going through, without exaggeration, thousands and thousands of pages of records. It’s tedious. It’s a lot of work. What worries me is that I’ve been at this almost a year and six months, and it’s still going on.”

‘Who do you go to?’

Gallagher’s query began by happenstance. A former student, Karl Von Derhaar, was a civilian working for the Police Department's crime laboratory when Von Derhaar’s boss, Sgt. Michael Stalbert, and two other officers went to Von Derhaar’s home in September 2020 to escort him for a drug test. Von Derhaar resigned and later received back pay.

Von Derhaar started searching government salaries online and found that Stalbert and several other officers were pulling hefty salaries. Some officers eclipsed $200,000 annually when shifts, overtime and off-duty security details were combined. Curiously, the highest-paid officers were mostly rank-and-file.

Although the police Public Integrity Bureau is supposed to investigate officer misconduct, Von Derhaar didn’t trust it with the information. So he called Gallagher’s UNO office.

“Who do you go to when you have suspicions like that? You can file a PIB complaint. But then, is PIB going to do anything? Is this going to come back to haunt you?” asked Von Derhaar, a forensic drug chemist.

Gallagher began filing a slew of records requests, which now number in the hundreds. He started with Stalbert, who is among the five officers that received FBI target letters.

If Stalbert was the spark, the pandemic was the fuel, said Gallagher, whose office walls are lined with colorful photos from travels to far-off lands: Burma, Cambodia, Kenya, Tanzania, Palau.

“Usually when school is out I’m gone. COVID kept me here,” he said. “Don’t know what other people did for COVID, but I started digging through these records.”

Skip Gallagher, a chemistry instructor, poses in office at the University of New Orleans on May 12, 2022. When not teaching, Gallagher spends his time scrutinizing public records, and his research has helped an FBI investigation into New Orleans officers who abuse special security details.

Gallagher discovered timesheets showing as many as 31 hours worked in a day. He’s identified 10 ploys that officers use to commit fraud, he said, and close to a dozen “sleep details," regular off-duty police jobs where attendance appears to be optional.

Lately, Gallagher has been reviewing data from license-plate readers to pinpoint officers’ whereabouts and match them against their timesheets.

“I’m really encouraged that the FBI has taken an interest in this. I truly hope that they look at little deeper,” Gallagher said. “It’s well over 50 officers who have serious payroll issues that would be difficult to explain. We’re not talking about an issue or two or three.”

‘A rare bird’

Gallagher, who moved to New Orleans 25 years ago to teach nights at UNO, has mixed it up with city officials before. A former Algiers Point Association president, he was involved in a neighborhood push to restore Mississippi River ferry service that was halted after Hurricane Katrina. He pressed the Regional Transit Authority over inspection reports for new ferryboats that sat idle, and he sued RTA over public records.

He parlayed that neighborhood activism into a run for state representative in 2015 but finished third in a six-person field, for a seat won by Gary Carter Jr. Gallagher netted 16 percent of the vote.

“He’s like, ‘If I don’t [run], who will?’ And the answer is nobody. He’s a rare bird,” said Fay Faron, a retired private investigator and close friend who ran Gallagher’s campaign.

Not everyone is thrilled with Gallagher’s recent sleuthing. Some challenge the severity of payroll abuses he says he has uncovered.

“These things can be much more complicated than they look on their face,” said Donovan Livacarri, attorney for the local Fraternal Order of Police. “My suggestion to everybody would be not to jump to any conclusions, and wait until all of the evidence is on the table.”

Even police give credit

Asked what credit the Police Department gives Gallagher for rooting out corruption on the force, the agency, in a statement, called his efforts “helpful,” while adding that an official investigation must occur before any officers are sanctioned.

“Every opportunity is a learning experience. We learned of gaps in the secondary employment system that may not otherwise have been discovered,” the agency said.

U.S. District Judge Susie Morgan, who is overseeing the Police Department consent decree, described the allegations as concerning at a hearing last month, though not an obstacle to clearing federal oversight.

Jonathan Aronie, the federal monitor, put a sanguine spin on the revelations. The scandal, “while quite disturbing, also reflects much about the change on the upside,” Aronie said. “A diligent citizen discovered much of this because New Orleans was transparent with its data.”

Anonymous calls, suspicious cars

Still, Gallagher paints a far more frustrating and perilous picture, saying City Hall stalled many of his early data requests for months. As he began soliciting more records and probing timesheets, Gallagher started fearing for his safety.

“I’ve had anonymous calls. I’ve been followed by multiple unmarked cars all the way to campus. I’ve had relatives and friends approached by uniformed officers - not in a threatening way but trying to find out information about me,” he said. “Multiple times.”

Gallagher, whose given name is Charles, considered going to Mississippi for awhile to get away from it all, to the home of his parents, a retired engineer and U.S. Navy veteran who did a tour in Vietnam, and a mother who wrote a newspaper column in Gauthier.

He ended up staying put, and the calls subsided last fall after the scandal blew up. The anonymous calls he gets now, Gallagher said, come from tipsters.

Gallagher still works his spreadsheets daily, in his office between classes or at night. He’s automated the process recently, he said, making it faster to birddog misconduct from high-earning officers.

“The behavior is still occurring, and it has to stop. You’re allowing active NOPD officers to continue to steal.

Now look, I’m a chemist, but I can read the law,” he said. “I'm not giving up now. I’m pretty tenacious.”