Remembering Stand by Me, 35 Years Later

On a sharp, sunny autumn day, I drove two hours south on I-5 from Portland to Brownsville—a population-1,800 town right off OR-228. I crossed the Calapooia River and pulled into the Linn County Historical Museum to meet Linda McCormick, a short, bespectacled woman in her 60s.

“This is where we keep the T-shirts,” McCormick said on my arrival, gesturing to a modest collection of merch in the museum lobby with designs inspired by the 1986 Rob Reiner film Stand by Me. Thirty-five years ago, the country came to know Brownsville as Castle Rock, the film’s fictional Oregon setting.

When McCormick and her husband moved to the area in 2005, she had no idea about the connection. “I think I’d only seen [Stand by Me] once on TV,” she admits. “It wasn’t like it was my movie.” But shortly after she arrived in town, two women at the chamber of commerce approached her to ask if she’d be interested in organizing an event for fans of the film. “I went home and watched it again and said, ‘You know, I’ll see what I can do,’” she recalls. One day, less than a month later, she opened the local newspaper to discover she had been named chairman of an event now celebrated annually, with blueberry-pie-eating contests, walking tours, screenings, and more. She estimates about 500 tourists visit each year for Stand by Me Day, and plenty more trickle in during off-months.

After we left the museum, McCormick showed me around town, highlighting key bars and alleyways, pointing to plaques, making sure to walk me past the (green-trimmed, largely unchanged) house that stood in for the protagonist’s.

The tree where Gordie, Chris, Vern, and Teddy situated their clubhouse

Image: Conner Reed

Then she led me up a hill to the tree where Stand by Me’s tween leads situated their clubhouse (“I have permission to come up here whenever I want,” she beamed), and I fell silent. There, right in front of me, was the image of Wil Wheaton climbing up to play poker with his friends, pulp magazine in hand. Off to the left, the heartbreaking shot where River Phoenix vanishes into thin air, made all the more devastating in the shadow of his untimely demise seven years after the film was released.

The tree is bigger now. I guess it would be.

For the uninitiated: Stand by Me, based on Stephen King's 1982 novella The Body, tells the story of 12-year-old Gordie (Wil Wheaton) and his best friends Chris (River Phoenix, in one of his first performances), Vern (Jerry O’Connell), and Teddy (Corey Feldman), each of whom weather unstable home lives. When news reaches the boys that a local teenager has been killed by a train, they set off on a summer adventure to find his body, hoping the act will bring them hometown glory. It’s a 1950s period piece narrated ruefully by a modern-day Gordie (Richard Dreyfuss), now a father and a writer.

One of Rob Reiner’s early directorial efforts (following This Is Spinal Tap and The Sure Thing), Stand by Me was a significant hit, pulling in more than $52 million at the box office on an estimated $8 million budget. If anything, its popularity has only grown in the three-and-a-half decades since it first hit theaters: multiple people involved with the production have noted a recent uptick in interest as the culture rides an ’80s nostalgia wave, which is especially funny when you consider that its original release coincided with a wave of ’50s nostalgia.

River Phoenix as Chris Chambers (left) and Wil Wheaton as Gordie LaChance, in one of the film's iconic Brownsville-shot scenes. The Blue Point Diner door still sits in the alley, a stone's throw from the original location.

The movie remains one of the popular and artistic peaks of Oregon cinema. Where Kindergarten Cop and Short Circuit feel dated, and the films of Gus Van Sant and Kelly Reichardt are pitched to a niche audience in the first place, Stand by Me endures across tastes and generations. Its critical reputation comfortably outstrips The Goonies on any review aggregator. The Oregon Film Office’s Film Trail, which identifies key Beaver State movie locations in an effort to boost film tourism, features a whopping three Stand by Me entries—more than any other film, and all, conspicuously, in Brownsville.

Andy Lindberg was a high school freshman performing with the Portland Civic Theatre when his mentor, Beth Harper, caught wind that a casting agent in Portland was scoping local screen talent. She helped students submit tapes, and Lindberg secured a callback.

“I was thinking maybe they were looking at me for Vern,” he recalls. Lindberg was only partway through reading the Stephen King story, and figured he might be in the running for the film’s sweet, bullied co-lead. A few days later, local musician Michael Allen Harrison chatted him up at a rehearsal. “He said, ‘Hey, I hear they’re looking at you for the vomiting guy.’ And I just kind of smiled and nodded,” Lindberg says. “And inside I was like, ‘Aw, shit!’”

Harrison’s “vomiting guy” prophecy came to pass. Lindberg landed the role of Davey “Lardass” Hogan, the protagonist of a campfire story Gordie tells his friends one night on their journey. In one of the film’s most memorable sequences, Gordie spins the ... visceral story of Hogan’s revenge.

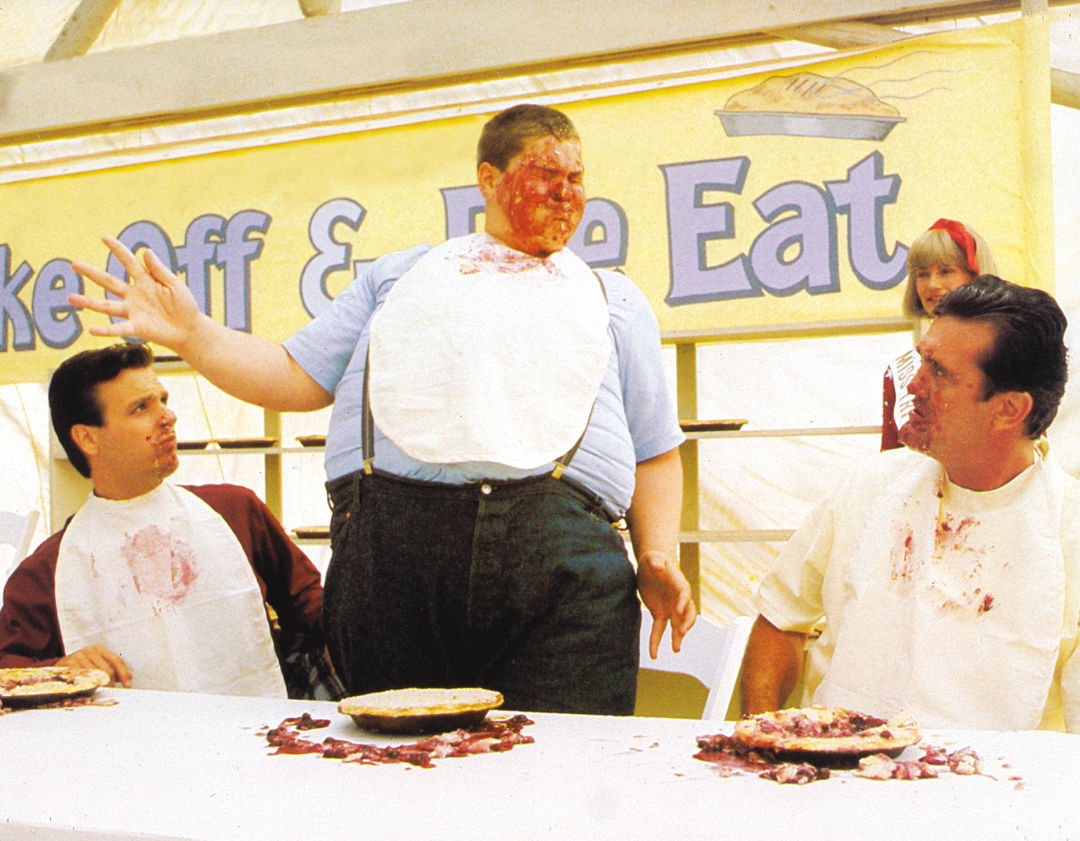

Andy Lindberg (center) as Davey "Lardass" Hogan

Constantly bullied for his weight, Hogan enters a blueberry-pie-eating contest attended by Castle Rock’s best and brightest. Early on, he pulls ahead, and the crowd chants his nickname in support. As his lead increases, it’s revealed that just before the competition Hogan downed a gnarly castor-oil-and-egg cocktail with plans to puke all over his tormenters. He does exactly that, and sets off what Gordie eloquently dubs a “barf-o-rama,” causing parents to puke on children, partners to puke on each other, and Lardass to feel like king for a day.

It’s tough to forget: the vividness of Wheaton’s words, the way Reiner captures his teeming juvenile imagination with horrifying, exaggerated visuals. As Lindberg recalls, the crew—working beneath tents in Brownsville’s Pioneer Park—went into the shoot with no firm plan to pull it off. “When we left on Saturday, they didn’t know how they were going to do the vomit on Monday,” he recalls. They tried blueberry pie filling in a pressure washer; it was a bust. For some of the smaller upchucks, they used caulking guns. For Lindberg’s monster pukes, though, the crew filled a 10-gallon cylinder with pie, connected it to a vacuum hose that snaked underneath Lindberg’s shirt, and masking-taped the hose to the side of his face. Three grips operated a “Wile E. Coyote–style plunger” to force the fake vomit from its cylinder. “Certain canned blueberry flavors trigger my gag reflex as a result of that,” Lindberg admits. “I’ve got a little posttraumatic pie syndrome.”

In all, Lindberg recalls a five-day shoot, during which he briefly met the film’s young stars. When Stand by Me hit theaters the next year, he went to the Portland premiere with his family at the now-defunct Southgate Theatre in Milwaukie, and had what he called “the closest thing to an out-of-body experience” he’s ever felt.

He never made another feature film. “There was a sobering reality that the market for overweight mid-teenagers was probably small,” he says, and he had no interest in moving to Los Angeles to find out. Instead, as an adult, he’s flitted between Portland and New York as a stage actor. Last year, he won a Drammy Award for his turn as Miss Trunchbull in Lakewood’s production of Matilda; this June, he took a job as executive director of Camp Westwind, a summer camp just north of

Lincoln City. He’s done half a dozen or so interviews about the film over the years, though the only time he’s been recognized in the wild was at a screening shortly after it was released. If this is his mark, he’s happy with it. “I’m fortunate that the only movie I’ve ever really been in is a good one,” he says.

Martin Hansen didn’t see Stand by Me in a theater; he waited several years before catching it on home video. Not necessarily unusual for a civil attorney living in Bend. A touch unexpected, however, when you consider that he operated the train at the center of the film’s most pulse-pounding moment.

A lifelong steam locomotive hobbyist—he started taking photos on and around railroads in his 20s, and the crews taught him how to operate the objects of his fascination—Hansen got a call in the summer of 1985 from a friend in McCloud, California, who he'd recently helped restore an engine. “He said the railroad had been contacted by a movie company,” Hansen recalls. “So he asked me to come down and help operate the train.”

Hansen showed up to help fire the train that nearly runs Gordie and Vern off its tracks at the film’s unforgettable midpoint, and found himself stunned by the pace of the production. “The movie industry is probably, next to the United States government, the most inefficient operation you’ll ever be around,” he grouses in hindsight. It took five days of shooting in Northern California—the location was selected for its enormous trestle over Lake Britton—to capture about 60 seconds of footage.

Jerry O'Connell as Vern (left) and Wil Wheaton running from the train operated by Martin Hansen

Trouble began with Reiner’s desire to skirt convention. Historically, oncoming train sequences had been shot into a mirror, leaving the crew and equipment out of harm’s way while locomotives barreled toward the glass and broke it. Reiner, however, employed a new $50,000 ultra-wide lens to shoot the train head-on, and tapped a grip to grab it from the middle of the track at the last possible moment. The guy froze. The lens (and camera) shattered.

When operations returned to mirror-shooting normal, Reiner was still determined to ratchet up suspense. Hansen and his fellow conductor were positioned behind the boiler of the train (you can catch their figures in the film; Hansen is on the right), making it difficult to spot the stunt doubles they were barreling toward. Reiner encouraged Hansen and his fellow operator to go faster and the stunt coordinator to start the doubles running later, quietly closing the gap between train and flesh with each take. “When we got to the end of the bridge, we would lean out to make sure we didn’t run ’em over. It was pretty nerve-wracking as far as I was concerned,” Hansen says.

It wasn’t trauma that kept him from watching the film when it came out, though. It just didn’t really cross his mind. The words “Stand by Me” meant nothing to him; when they were shooting, it was still called The Body. (The studio changed the title in response to fears it might sound too sexy or like a typical Stephen King scare-fest.) When he finally got around to it, he couldn’t help but laugh at his climactic moment.

“As an operator of a train, you never want to see any living object in the middle of the track. I don’t care if it’s a person, a cow, a bunch of kittens—it scares you,” Hansen says. Trains that size need about a mile to come to a complete stop, but any sensible engineer would do everything in their power to slow down if they found themselves barreling at four preteen boys. “Obviously the train crew sees them, because we’re blowing the whistle, but we’re charging at them. We’re pouring out smoke, which means we’re accelerating. It’s like we’re trying to kill the kids.”

With a shrug, though, he admits that the plumes of smoke look impressive. “That was the Hollywood part, I guess.”

For her 40th birthday, Linda McCormick donned pioneer dress and, over three days, walked 60 miles of the Oregon Trail to commemorate its 150th anniversary. She counts the experience as one of her life’s most satisfying. When asked what she loves most about organizing Brownsville’s Stand by Me celebrations, she says it’s facilitating that same sense of near-sacred reanimation for others: an Australian man who flew 8,000 miles to touch a post that Wheaton and Phoenix touch in the film; Japanese tourists whose parents came to love the movie as a glimpse into post–World War II America.

“What’s funny is I never really thought about going to see where a movie was filmed before I started meeting up with people here for Stand by Me,” she says. But the fans have turned her into “a nut.” On a trip to Northern California with her husband, she made him detour to the no-longer-in-use trestle over Lake Britton, where she stole a railroad spike and pocketed some bright red soil.

Stand by Me may not have been Linda McCormick’s movie when she was

approached by the Brownsville chamber of commerce all those years ago, but it’s always been mine. I bought it on DVD at Fred Meyer when I was 10 and had it memorized within weeks; I’ve probably seen it more than anything else ever made. The purple vomit, the screaming train, the tree: they knock around my middle school memory as vividly as dances I actually attended or campfires I actually built.

The film’s most famous line is, in many ways, also its mission statement: “I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was 12. Jesus, does anyone?” There’s its empathy, crystallized, plus a distillation of the multitudes that spring from its deceptive simplicity. Stand by Me is about a bewildered adult fumbling for the purity of boyhood, and it’s about bewildered boys wielding their youth as a shield against the unbearable darkness of growing up. It’s about the vertigo and the mundanity of loss, all personified in the last endless summer before your world starts to atomize.

It’s something I watched in the Oregon wilderness with my friends when I was 12, because it felt like it was both speaking directly to and directly above us, housing something like wisdom between its dick jokes and singalongs which we couldn’t quite glean.

I can’t say I’ve had a movie grip me in the same way since. Jesus, can anyone?