The Fight to Preserve Pike Place Market Isn't Over

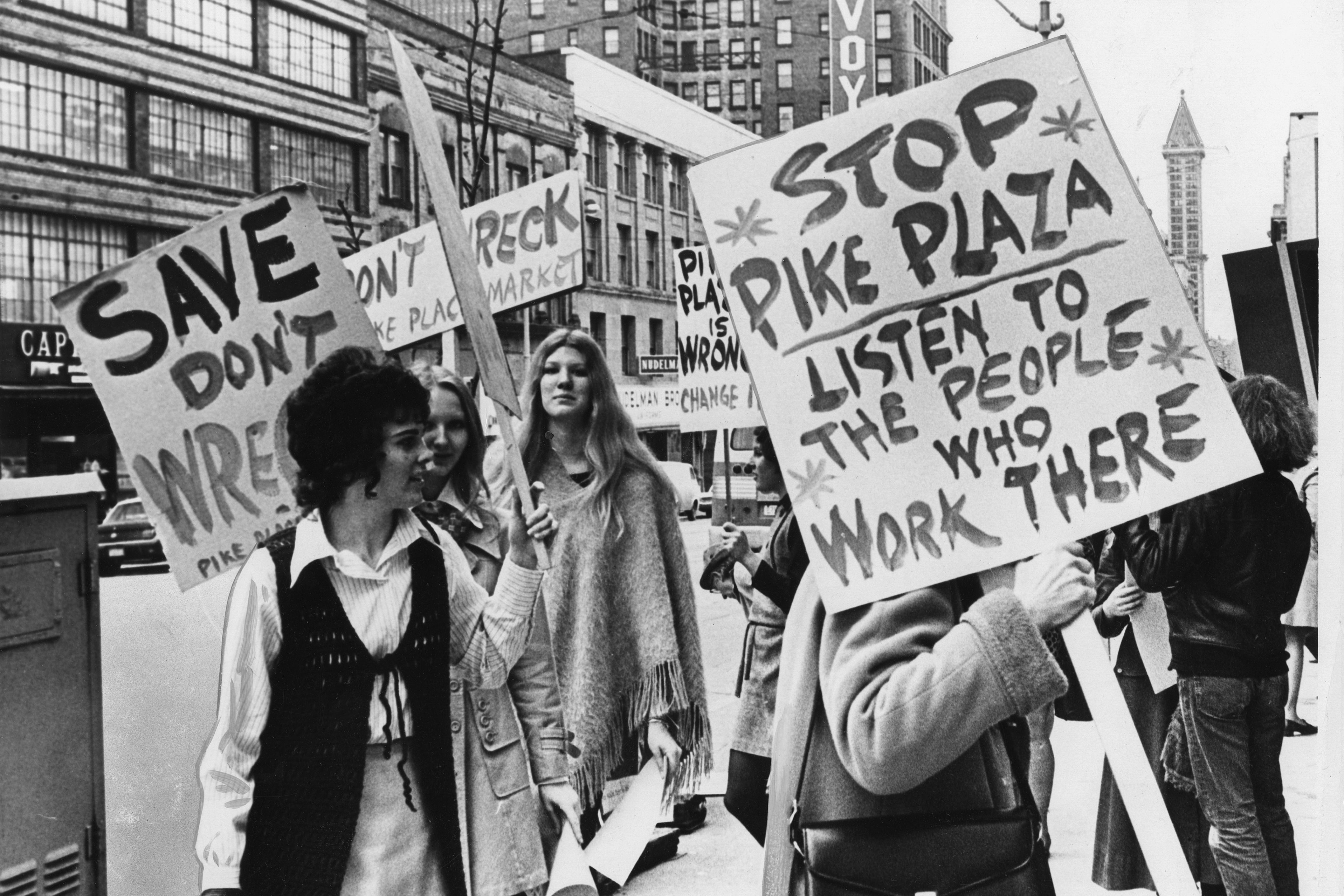

Friends of the Market protest at the Arcade Plaza building on February 11, 1971.

Image: MOHAI / Webber, Phil H.

The cross-outs give it away. Or maybe it’s the carets. For all Victor Steinbrueck’s diplomatic words, the University of Washington professor wrote in a fury while on sabbatical abroad in 1968.

From the renowned architect’s fountain pen flowed the lifeblood of Pike Place Market, a ramshackle hive of commerce that Steinbrueck, perhaps before anyone else, deemed a Seattle institution. His illustrations published that year captured the teeming caverns of an L-shaped building perched precariously above the Sound. The community was also in a different kind of danger then. The city had slated the neighborhood for parking garages, apartment towers, a hotel, and a rehabbed market as part of “urban renewal”—destruction and displacement, in Steinbrueck’s mind, dressed up as revitalization.

In letters from England to politicians and developers back home, Steinbrueck stressed that the mercantile blocks were a vital area for low-income shoppers, that they were essential to the city’s character. Early drafts show that he agonized over his tone, liberally wielding editorial marks to soften his language and convince recipients to help save the institution he cherished. “P.S.,” he nudged at the end of one very civil note to mayor J.D. Braman. “Because we have lost all of the struggles for amenities in Seattle in the past, it does not follow that we must lose this one.”

The city’s plans alienated Victor Steinbrueck.

We wouldn’t. Even after Seattle City Council approved an only slightly more palatable redevelopment plan in 1969, and after the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development allotted more than $10.5 million for the project, Steinbrueck and other Friends of the Market activists kept fighting to maintain the spirit and structure of the neighborhood. In 1971, they started an initiative campaign to create a seven-acre historical district and 12-person commission to supervise its uses. “Keep the Market” supporters gathered more than 25,000 petition signatures in three weeks, ensuring the matter would be put to ballots. On November 2, after months of advocacy work with Alliance for a Living Market, the Friends triumphed. Initiative No. 1 passed with 59 percent of the vote, thwarting glossy construction. The citizens of Seattle had preserved the market as they knew it.

Kate Krafft thinks we’ve gotten complacent. The Friends of the Market president doesn’t want to be negative—celebrations of the anniversary have dotted the fall calendar—but she also doesn’t believe local leaders grasp the urgency of the market’s continued preservation. “I’m pretty fed up with city government,” she says.

As Krafft describes it, Pike Place Market rests on three organizational legs: Pike Place Market Preservation and Development Authority, which owns and manages most of the property; Pike Place Market Foundation, a nonprofit that runs health and housing programs; and the Pike Place Market Historical Commission, the 12-person body that the 1971 vote created to sustain both the tangible and intangible parts of the landmark. “It didn’t just ask to preserve a place and a group of buildings,” she says. “Its intention was to preserve the character of the neighborhood, of the community.”

In practice that often means deliberating over the finer points of, say, bar finishes, ramp tiling, and produce prices. It’s the kind of attention to detail Victor Steinbrueck and company would have appreciated when advocating for the body’s formation. Mayor J.D. Braman called them “nitpickers” for a reason.

Christine Vaughan says the market “gets in your blood.”

Image: Mac Holt

Yet, unlike the market’s other pillars, the commission is a bit wobbly these days. Only nine of its city-appointed 12 seats were filled as of late September. Three members have stayed on past the expiration of their three-year terms while potential successors await confirmation from City Hall. Friends of the Market, which nominates two positions, submitted four potential replacements for member Christine Vaughan to the mayor in February. No one had been selected as of this writing. “They’re failing in that duty,” Krafft says.

Sarah Sodt, the city’s historic preservation officer, cites the coronavirus pandemic as one reason for the holdup on the city’s side, along with the usual levels of review that come with board and commission approvals. Commission chair Lisa Martin agrees. She says that it can be particularly hard to find volunteers during trying times. Still, she adds that the appointment process is “very bureaucratic” and “bogged down,” and her predecessor, Vaughan, notes that filling positions has been a problem since 2017. “This predates Covid,” she says.

Vaughan worries that the appointment delay will lead to mass turnover at some point. Outgoing older members won’t be able to pass on the regulatory savvy that has protected the farmers market for decades and kept chains from nabbing storefronts near the stalls where Vaughan has sold flour sack dish towels, the kind “your grandmother used to use,” for three decades.

She has another gripe too. Once shutdown orders shuttered businesses and instated virtual meetings, Seattle City Council approved an emergency ordinance that allowed the city’s historic preservation officer to review and approve minor changes across all eight of Seattle’s historic districts. The policy, Sodt says, was intended to expedite the permitting process for business owners, tenants, and property owners during an unprecedented crisis. It will remain in effect until 90 days after the city’s state of emergency has been lifted.

The ordinance was understandable initially, Vaughan says, as the government learned how to function remotely. Zoom is second-nature by now, though. It’s at least a little awkward to check the commission’s powers as Seattle celebrates the group’s codification. The city, after all, was one of the parties behind that wrecking ball 50 years ago. “Is that a danger right this minute? Probably not,” says Vaughan. “But times change, and administrations change.”

Businesses change, too. When Sol Amon first started at Pure Food Fish Market, he and a couple other workers would take a truck down to the waterfront, load it up with fish and ice, and drive it back up the hill to unload. Today, his granddaughter Carlee Hollenbeck oversees an operation that flies in salmon from Alaska, snappers from Thailand and New Zealand, and scallops from Boston. (The ice machine is onsite now.)

“Born and raised” in the market, Hollenbeck was extremely close with her grandfather, who died in September. She’s honored him by continuing his life’s work, which involved more than just fishmongering. Every April 11 in Seattle is Sol Amon Day in recognition of his support for low-income, senior, and food-insecure populations in the close-knit neighborhood. “It’s really like a sacred space,” Hollenbeck says.

Still, she’s adapted the fourth-generation business to the needs of a twenty-first-century customer. She helps fulfill online orders, overnighting fresh fish to buyers across the country. The digital revenue sustained her seafood shop when foot traffic crawled early on in the pandemic.

Christine Vaughan knows the Pike Place Market Historical Commission’s guidelines must periodically change to meet the shifting needs of visitors and address disputes across the community: between landlords and tenants, big businesses and small. But the power to impose these adjustments must remain where it’s been since 1971: with the merchants and residents, property owners and activists, that form the commission. The people. “If we can make it work at the market,” she says, “there’s hope for the rest of the world.”

As Victor Steinbrueck knows, a little revision can go a long way.