When Charlene Crump Sanchez tested positive for the coronavirus last year, it seemed certain she would recover quickly.

She was just 45 and in good health. After working long days at St. Margaret’s nursing home, she still cooked up a storm and was still able to keep pace with her 12-year-old daughter, Star.

“Nothing kept her down,” said her older daughter, Bresha Crump, 26, recalling how her mom got a knee replacement and walked on it the very next day.

Still, Bresha recalls, the COVID diagnosis was frightening. The pandemic was brand new. Eleven days earlier, New Orleans had mourned its first known coronavirus victim.

Then local hospitals started to fill up. Many of the people most vulnerable to the virus, then as now, were the elderly. To date, the average age for all Louisiana coronavirus victims is 74.

Crump Sanchez, three decades younger than that state average, died from the virus on March 25, 2020.

Bresha got the news and fainted on the front lawn. Within the hour, hundreds of people took to social media to express their shock. “Oh my God, Nooooooo,” friends posted. “This one hurts.”

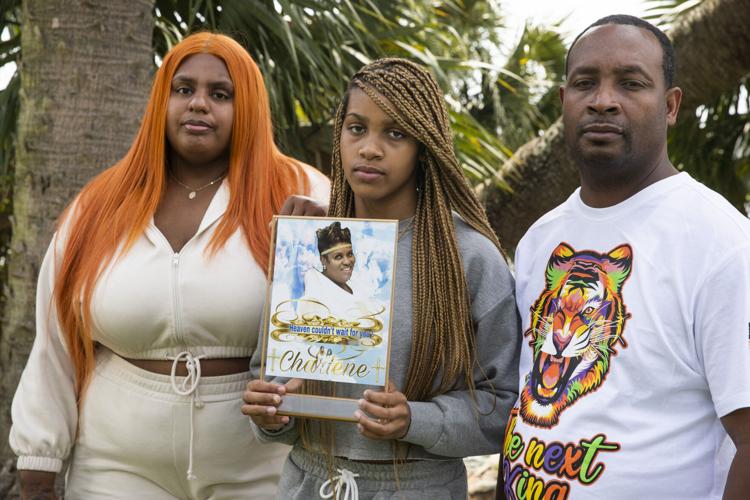

Bresha Crump, left, poses with her father Troy Sanchez, right, and her sister Star Sanchez, 13, as Star holds a photograph of their late mother, Charlene Crump, at City Park on May 1. Charlene Crump died of COVID-19 complications in March 2020. She was just 45.

Her death is an example of how coronavirus has impacted Black communities differently, killing outsized proportions of young and middle-aged Black people. Even as cases surge among unvaccinated people due to the delta variant, experts believe that most patterns of the last year are likely to hold true, because they are based on longtime workplace, demographic and healthcare-system dynamics.

Because it was a nice afternoon in March, Katrina Llorens Joseph and her husband Albert decided to sit outside for lunch at the Subway restaur…

Louisiana is home to twice as many White people as Black people. But last year, about two-thirds of the Louisianans under 65 who died from COVID were Black. The situation is flipped for COVID victims over 65, two-thirds of whom were White, according to data from the Louisiana Department of Health.

What that means is the per-capita death rate for younger Black adults for last year was nearly four times the death rate of Whites of the same age, while death rates for Black seniors were roughly equal to those of Whites ages 65 and over.

Exposure a key

There’s no single explanation for the differences.

The prevailing theories are rooted in Louisiana’s deep structural inequities, which create different living and working conditions for Black and White residents — and elicit different responses from the healthcare system for those who get sick.

Many researchers believe workplace infection is the biggest factor. Black workers are more likely to have frontline jobs that expose them to the virus. And if they become infected, they are more likely to bring it home to more dense, multigenerational households in predominantly Black neighborhoods, where residents have less access to emergency rooms and primary-care doctors.

“Blacks in younger age ranges are more likely to have the type of jobs that put them at risk,” said health-equity expert Thomas LaVeist, dean of the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine. He ticked off a few of those jobs: healthcare providers, transit drivers, grocery clerks, kitchen crews and service workers of all types.

Epidemiologist David Michaels, a former head of the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration, also links higher death rates for younger Black people to higher rates of workplace infection.

“People who are not exposed to COVID-19 don’t get sick,” said Michaels, now a professor at George Washington University.

Months into the pandemic, state data indicated that Black people were contracting the virus at three times the rates of White people. The official database no longer shows that sort of disparity — even for majority-Black parishes such as Orleans, where Black people make up 60% of the population but only 52% of cases, and East Baton Rouge, where Black people make up 46% of population and 45% of cases.

But because of the pandemic’s large number of undiagnosed people — 4.8 people infected for every reported single case, according to a National Institutes of Health study published last month — LaVeist believes that Black infection rates, most stemming from the workplace, have “stayed at a higher level” undetected in official data.

Months into a pandemic that has ravaged social clubs, churches and other gathering spots for thousands of Black New Orleanians, City Councilme…

Infectious-disease researcher Greg Millett, vice president of the Foundation for AIDS Research, found in a study of disproportionately Black counties that as unemployment rates increased, COVID rates went down. “If you’re not working, it reduces your risk,” he said.

A web of factors

African American doctors in local hospitals are studying COVID disparities carefully. Dr. Krystle Pew, a pulmonary and critical-care medicine fellow at LSU School of Medicine who studies health equity, has found that Black patients were more likely to be ventilated. She is trying to determine the reasons for that.

Early in the pandemic, some outspoken experts hypothesized that the racially disproportionate impacts of COVID were largely due to higher rates of comorbidities like diabetes and hypertension among Black Louisianans. Research has shown that the role of such underlying conditions in COVID cases is one piece of a complex societal puzzle. “We had to take a step back and broaden our view,” Pew said.

A few different analyses, including one done in Louisiana last year by Dr. Eboni Price-Haywood using data from Ochsner Health Center, have found that, once hospitalized, Black COVID-19 patients were less likely than others to die, despite higher rates of underlying conditions. Another 2020 study from a Bronx hospital also found no difference in mortality rates between Black and White patients.

Price-Haywood also found that Black patients were more likely to have been diagnosed with COVID for the first time in the emergency room.

Pew attributes that to life circumstances.

“Many Black workers do not have the luxury to say, ‘I will not go to work today,’” she said. “So many of their first interactions were in the emergency department. They came in later.” Trying to fit a clinic appointment into a workday can be particularly hard for those who don’t have a regular primary-care doctor, she said.

Default set to White

Another contributing factor: Pew and her colleagues noticed more Black patients coming in with low blood-oxygen levels, because their oximeters — the crucial little pandemic machine that clips onto a finger — gave a false reading. As it turns out, darker skin pigment affects the accuracy of oximeters, which use light beams to estimate pulse rates and blood-oxygen levels. Calibrated for light skin, oximeters gave falsely high rates in darker-skinned people, obscuring the condition known as hypoxemia — and likely delaying medical treatments like supplemental oxygen.

A study published in December in the New England Journal of Medicine found that, compared with White patients, Black patients were three times as likely to have severe hypoxemia not detected by pulse oximeters. In February, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued an alert to patients and healthcare providers about the device’s accuracy.

Long-used medical algorithms that guide doctor’s decisions also often amplify risks for Black patients, overlooking lower lung capacity, making them less likely to be qualified as kidney donors or to be steered away from surgery or more aggressive screening procedures, according to research published in August in The New England Journal of Medicine. Through what’s known as “race correction,” diagnostic algorithms are regularly used by physicians to guide clinical decisions.

LaVeist, from Tulane, remembers being in a hospital and seeing a radiology tech plug a “race corrected” formula into a machine before scanning a Black patient — relying on an algorithm that assumes greater bone density for Black people. LaVeist sees parallels in discussions about COVID’s racial disparities, which he attributes largely to workplace infection. “But some people are operating from the assumption that there’s something about African American people that’s causing the difference,” he said.

Dr. Angela McLean, a professor of clinical medicine at the LSU School of Medicine and a native of the Lower 9th Ward, saw how hospital access made a difference. From the Lower 9 or New Orleans East, travel times to a hospital could be so long that breathing became considerably more labored in transit, she said. “I heard stories of how it would take an hour or so to get to the hospital, with oxygen levels dropping.”

McLean also believes that the pandemic took a greater toll on COVID-infected people who lacked relationships with primary-care physicians, a group that skews disproportionately Black. “If you already know this patient, you know that they sound a little bit more short of breath than usual,” she said. “Or you’d already know that this patient would not be calling if they weren’t really sick.”

When Thomas LaVeist, head of the Tulane School of Public Health, thinks about the spread of the coronavirus in New Orleans, he conjures up a “…

Similarly, Angela Chalk, the founder of Healthy Community Services, began collecting stories when Black neighbors — even those she knew to be persistent — sought care for COVID and were turned away at least two times.

Pew believes in looking back at those moments, to examine how healthcare providers determined hospital admittance or treatment.

“We don’t treat everyone the same,” Pew said. “Two people who look different can present to the hospital with similar numbers and similar presentations, and one gets admitted and one gets sent home.”

In the case of Crump Sanchez, she was sent home twice by doctors, then admitted to a hospital, where she died.

'Not really for the old'

Crump Sanchez’s family assumes she contracted the virus at work. When her name was added to the grim roster of COVID deaths compiled by the Orleans Parish Coroner’s Office, a full third of the list — 21 people, at the time — were younger than 60.

All were Black.

“When Charlene died, it became clear that the coronavirus wasn’t really for the old people, like they had said,” said Crump Sanchez’s close friend, Dana Pajeaud, 47.

“It’s unbelievable to me how many people we know have buried people young over the past year or so,” she said.

The same pattern of racial disparities by age holds true nationally, according to an extensive study led by Mary Bassett, a professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Overall life expectancy in the U.S. was reduced by 1.5 years because of the virus. Because of higher COVID-19 mortality rates — especially higher rates at younger ages — the national decrease in life expectancy in 2020 was three times higher for Black people, whose life expectancy at birth declined by nearly three years, from age 74.7 to 71.8 years.

Since younger COVID victims are more likely to have young children, Bassett found these deaths especially damaging.

“Robust evidence documents the transgenerational adverse impacts of parental death at younger ages on their children’s economic and health trajectories,” the study noted. “Our data underscore that COVID-19 will likely exacerbate these harms.”

Star Sanchez, now 13, thinks back to the way her mother over-celebrated every holiday, decorating the house, cooking stuffed shrimp and peppers, and picking movies to watch together. “What wouldn’t she do?” Star said.

Her older sister Bresha said that she still doesn’t understand why her mother died so young. But after receiving 25 years of her mother’s love and devotion, she is dedicated to nurturing her little sister in the same way.

“When I talk to God now, my prayers are totally different,” Bresha said. “I ask Him for my mom’s characteristics to help with Star. Because I want to raise Star like my mom raised me.”