The email seemed urgent. The subject line read “important notice,” and Burnett paused grading to read it. Then, she froze in her chair. After four months of her skirmishing with the school’s administration, Collin College was going to terminate her contract.

She partly expected it, but to see the words in black and white still shocked her. “It was a real blow. I mean, it was shattering,” Burnett said. “Teaching at Collin College is my dream job.”

Collin College had already terminated at least two other professors earlier this semester. Although each case panned out differently, she couldn’t shake the similarities. All three are women. All three had spoken out against the college’s COVID-19 protocols. Unless college administrators change their minds or the teachers succeed in their pending appeals of the dismissals, they will each work their last day May 14.

But Burnett’s dispute with the school had been going on longer. It all started with a tweet. In October, she posted her thoughts about the vice presidential debate on Twitter. Mike Pence, then vice president, repeatedly talked over the female moderator. Burnett wrote that he should shut "his little demon mouth up.”

A well-oiled “outrage operation,” as she calls it, immediately kicked into gear. The right-wing media machine picked it up, with one Fox News headline reading “College Professors Let Loose Profane Criticism of Pence during VP Debate.” The ultra-conservative Campus Reform website ran with the story, embedding several of Burnett’s tweets. The professor gave her school’s administration a heads up that they may be hearing from journalists.

Instead of defending her, college officials distanced themselves. Although they didn’t name her, Collin College condemned Burnett’s “hateful, vile and ill-considered” tweet on its website. Meanwhile, district President Neil Matkin sent staff an internal email complaining he’d received numerous calls for her termination, including from legislators.

Burnett said the way Matkin handled the issue put an even bigger target on her back. His response legitimized, in other people’s eyes, the idea she didn’t deserve support or protection; soon after, she said the harassment “kind of went into overdrive.” Obscene messages, some of them violent, flooded her email and social media inboxes, and some wormed their way into her work phone’s voicemail.

In a way, Burnett knew the drill. She’s writing a book about culture wars. Still, the historian said, “It’s kind of exhausting to be in one.

“I knew what to expect, but I didn’t know what that would feel like,” Burnett said. “I was not ready for what it would feel like to be at the center of that ginned-up outrage, and it was really, really rough. It was frightening, and it was disorienting, and it was rough.”

*

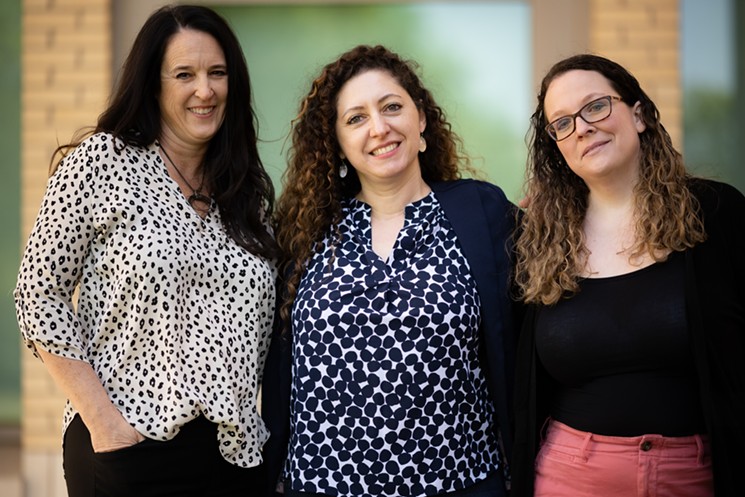

Officers of the local TFA chapter. From left to right: Dr. Suzanne Jones, Lorena Rodriguez and Audra Heaslip.

Mike Brooks

Jones and Heaslip are among the three founding officers of a local Texas Faculty Association chapter, an educational advocacy group. The organization planned to have its first meet-up event to recruit new members the same day Jones and Heaslip learned they would be dismissed. In addition, Jones was informed that Collin College declined to renew her multi-year extension because the school’s name had appeared at the bottom of a 2017 open letter she’d signed calling for the removal of Confederate monuments.

It wasn’t always this way. In the past, Collin College didn’t stymie its faculty’s speech, Jones told the Observer in January. “It was accepted that, of course, we don’t always agree,” she said. “It was a great environment, and we just don’t have that anymore.” The school’s own policies require administrators to “uphold vigorously the principles of academic freedom and to protect the faculty from harassment, censorship, or interference from outside groups and individuals.” These days, though, many employees say they’re terrified to speak out, and some who do are shown the door.

The school pushed out another professor on Jan. 28. Like Jones and Heaslip, English professor Barbara Hanson said she wasn’t afforded due process and had no disciplinary warnings to indicate she’d fallen out of favor with the school. She kept quiet about the ordeal until late last month, when she revealed at a board of trustees meeting she, too, had been targeted.

Unlike the others, though, free speech issues weren’t cited as reasons in the decision to deny her a multi-year contract. Hanson had applied for two administrative positions within the school, which officials later claimed indicated she was no longer interested in teaching. They’d also used three negative student evaluation comments, out of scores of positive ones, from the fall 2020 semester to try to illustrate that point. Hanson said they cherry-picked comments from teenagers who were enrolled for the first time in asynchronous learning, in which course material is put online but there’s no set time for meetings between students and teachers. Without a clear understanding of what college entailed, the students complained she didn’t host class meetings.

Hanson taught at Collin College for three years, but she’s spent three decades working in community colleges. She has a great deal of respect for them, too, respect she feels she wasn’t afforded. “I was just doing my job, I thought, so I was really hurt to be so disrespected and feel I was not valued,” Hanson said. “I felt like a piece of furniture: ‘We’re done, thank you. Throw you out the door.’”“It was accepted that, of course, we don’t always agree. It was a great environment, and we just don’t have that anymore.” - Suzanne Jones, professor

tweet this

Last week, the Allen American reported that a Collin College administrator, Linda Wee, has accused a provost of retaliation and racial discrimination. In one formal complaint, Wee wrote that as the college’s sole Asian female director, she's been the target of “concerted efforts to make the work environment intolerable.”

When asked for comment, Collin College’s director of marketing and communications Marisela Cadena-Smith sent a statement that defended the school’s handling of the terminations. “Collin College has policies and procedures to address employees’ concerns and rights, including a well-established process for conducting administrative appeals for issues such as the non-renewal of a faculty contract,” the statement read. “The college has and will continue to follow those policies and processes. Therefore, out of respect for our employees’ privacy, the college will not provide further comment on this matter.”

Founded in 1985, Collin College is a public community college district that serves more than 58,000 students throughout its nine campuses. Its colors are blue and white, and its mascot is the cougar. According to its website, the district plans to open two more campuses later this year. Three incumbents on the board of trustees, including Chair Bob Collins, are up for reelection on May 1.

*

Burnett wishes her grandmothers had lived to see her land a full-time professor job. Her mom dropped out of high school before earning her GED through the local community college, and her maternal grandparents had a sixth-grade education. After she was born, Burnett's dad also enrolled in community college, which allowed him to move from his position as a gas station attendant to a white-collar job. Higher learning means the world to Burnett, who, despite growing up in a lower-middle-class family, was able to attend Stanford with the help of a California state grant.While a student, Burnett soaked up as much knowledge as she could, and she credits the experience with molding her into the person she is today. It takes a few generations of education for a family to move from the working to the middle class, she said, and she hoped to hold that door open for first-generation and working-class students from backgrounds like hers.

Burnett earned a doctoral degree in humanities/history of ideas because she wanted to teach at the community college down the street: Collin College. “Community college, in particular, means a lot to me, and it’s meant a lot to my family, and it’s meant a lot to working-class families in the 20th century in America,” she said. “That was just transformative for my family and certainly for me, and I feel that when you’ve been blessed, the best thing to do is to turn around and share that.”

Despite her passion for teaching, at least one state lawmaker pushed to oust Burnett following her October tweet about the vice president.

Shortly after the ordeal, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) caught wind of Burnett’s Twitter fiasco. The nonprofit group requested documentation of the communications that Matkin had with “legislators” asking for her termination. The school fought FIRE, petitioning the state’s attorney general to prevent the records’ release. Ultimately, the school had to hand them over.“Community college, in particular, means a lot to me, and it’s meant a lot to my family, and it’s meant a lot to working-class families in the 20th century in America." - Lora Burnett, Collin College professor

tweet this

Although Matkin complained of hearing from multiple lawmakers, the school coughed up a single screenshot of a text message conversation between him and state Rep. Jeff Leach, a Republican from Plano. In that exchange, Leach asked Matkin whether taxpayer dollars funded Burnett’s salary. Matkin said, yes, they did, adding that Burnett had already been “on his radar.” Records showed the school paid more than $14,000 to hide the text message exchange, an expense that Burnett said was also footed by taxpayers.

Later, Leach launched a Twitter war with Burnett after she commented on one of the posts he’d made during February’s winter storm. The week before she was terminated, Burnett criticized Leach for trying to get her fired. The lawmaker then replied with a GIF of a ticking clock, ostensibly celebrating that she would be let go.

Many Republicans have accused universities of being liberal bastions unwelcoming to conservative thought, but Burnett said those people are just “telling on themselves.” Burnett said she never preached her personal beliefs from the lectern. “I can’t imagine using the classroom as a bully pulpit for my own small opinions,” she said.

Rather, Burnett wants her students to think about literature, art and the “treasures of the humanistic tradition,” from Herodotus to American historian Richard Hofstadter. “I wouldn’t waste [my students’] time, or mine, on something as ephemeral as the politics of the moment,” she said.

*

Suzanne Jones had signed the petition calling for the removal of Confederate monuments, but Collin College history professor Michael Phillips had co-authored the open letter. School officials gave Phillips a verbal warning after the letter was published, but he was never formally disciplined. Like Jones, Phillips doggedly challenged the school’s COVID-19 reopening plans, even speaking to media outlets about his worries. He had good reason to worry, too: Soon, a student and a faculty member would die from the disease.

For months, Collin College fought against implementing a COVID-19 dashboard to keep track of cases on campus. Phillips told KERA in November that once a cafeteria worker had contracted COVID, only a small number of people were told. Faculty and staff, meanwhile, were largely left in the dark.

Then in October, the coronavirus killed a Collin College student, Rogelio Martinez. A month later, a faculty member died.

It was nursing professor Iris Meda’s first semester teaching at Collin College, and The New Yorker reported she thought that classes would be held online. But the school pushed her to teach in person where keeping a safe distance from students wasn’t possible. The Harlem-reared Meda, who once tended to sick prisoners as a jail nurse, died from COVID-19 shortly after one of her students tested positive.

Phillips blasted the “callous” way the school’s president informed employees of Meda’s death: in the 22nd paragraph of an email titled “College Update & Happy Thanksgiving!” In the email, Matkin didn’t acknowledge the nursing professor by name, which also made Phillips bristle. Meda was Black, and Phillips said the president’s unwillingness to “say her name” speaks volumes.

Later, Phillips wrote a resolution requesting the school honor his colleague. He asked for a scholarship to be named after Meda, for her pogrtrait to be displayed and for her family to be honored during a school event. Faculty Council passed the resolution in January, but Matkin didn’t budge.

More generally, Collin County itself is an atmosphere shaped by right-wing extremism, Phillips said. A large number of the insurrectionists who participated in storming the U.S. Capitol in January call it home. Collin College, meanwhile, is pushing to sanitize student thought by removing professors who speak out against racism and those who voice concerns about the pandemic, Phillips said.

“We are doing a terrible disservice to students as citizens if this is what we model at the college campus,” he said. “And there doesn’t seem to be a real clear understanding of free speech among the leadership of this college at all.” In February, FIRE named Collin College as one of the top 10 worst schools for free speech.

After months of silence, Matkin sat down for an interview with D Magazine last month and dismissed professors’ push for stronger COVID-19 policies. He told the reporter that if he could have done it over again, he wouldn’t have tried to “bring logic to an emotional argument.”

Reading that floored Phillips. “That is the oldest sexist trope in the book: Men are supposedly logical, women are emotional,” he said. “And that was so striking particularly given … the four women whose jobs are being eliminated with no due process for simply exercising free speech.”

*

Even though Burnett dedicated herself to ensuring her students had an excellent learning experience, it had been a tough semester from the get-go. On the first day of classes in January, she had received a Level 1 disciplinary notice, indicating a potentially fireable offense. The school dinged her for yet another tweet, this one about a former Collin College professor who recently had died of COVID-19. Burnett acknowledged his passing but didn’t realize he hadn’t worked at the school for a couple of years; she said his name was still listed on the school website at the time of her tweet, after all.

Still, in their written warning, administrators said all Collin College staff should strive for accuracy when making factual statements. And the timing of the warning also sent a message, Burnett said: “It felt like a deliberate attempt to demoralize me.”

Soon after, Burnett realized the school was splitting hairs to find a reason to let her go. So, she asked her attorney to send administrators a letter communicating her concerns. They also told the school to preserve pertinent records. Then, Burnett said, Matkin deleted his personal Twitter profile and she received her termination notice.

After months of fighting with Collin College, Burnett desperately wants to keep her job. But should she lose it, she doesn’t see herself teaching in the future. She’d already been out of the workforce for a long time to raise a family, and it was hard enough to land this job in her 50s. Ageism and sexism still permeate American society, Burnett said, and she already felt she’d “scaled Mount Everest” to attain her current position. “I certainly have the ethical fortitude,” she said, “but I don’t have the emotional energy to put myself on the job market again.”“We are doing a terrible disservice to students as citizens if this is what we model at the college campus." - Michael Phillips, history professor

tweet this

Even though it cost her a job and more, Burnett said she couldn’t remain silent while the school tried to muffle faculty voices. She has remained active on Twitter following the Pence-tweet debacle and continues to speak to the media about what’s happening with the school.

Officials want faculty to “crawl back into a shell” and avoid attracting attention, but Burnett said she couldn’t stay quiet. If she’d muted her Twitter account just to keep her job, the school would have won. Her colleagues, meanwhile, would have heard the message loud and clear: If they stand up, they’ll soon get mowed over. Collin College’s civil war is also costing its students, Burnett said. She’s heard from many who adored her class, and not being able to help history come alive for others pains her.

In the meantime, Burnett plans on freelancing and finishing her book, even though writing doesn’t pay well. Now a casualty of a micro-culture war herself, Burnett wants to chronicle her firsthand experiences. “I do love teaching, but I was a writer long before I was a college professor, so I can be just a writer again … It won’t pay the bills,” she said, laughing dryly, “but it’ll let me use my voice.”