“There are no mothers-in-law in ballet,” said George Balanchine, meaning there are some details you can’t express through dance steps. Actually, a lot of details. If you’ve ever watched dance and thought “what’s going on here?” you wouldn’t be alone. Even the best-known ballets can be baffling to a newcomer: a woman has been turned into a swan, you say, and can only be returned to human form by a man swearing his true love to her? And then her doppelganger comes along, played by the same dancer, but it’s actually an evil sorcerer’s daughter? You what now?!

Big ballet companies, not wanting to alienate audiences, stick with the same titles so they don’t have to explain what’s going on. But no one wants to see the same five stories for ever, nor feel stupid by not understanding what’s happening. “Be sure to read the programme beforehand” is critic’s shorthand for a very confusing story. But Scottish Ballet founder Peter Darrell used to say that if you have to read the programme, a ballet has failed in its job.

Historically, ballet made use of mime for exposition, but you need to know the codes (hands twirled above the head means “dance”, two fingers held aloft is “promise”) and it’s fallen out of favour. Similarly bharatanatyam, the Indian classical dance form, has a lexicon of hand gestures called mudras, with specific meanings, some easy to guess, some less so.

Plenty of dance comes without narrative, or even theme. Its concern may be spatial, geometric, musical or rhythmic (think of Merce Cunningham or Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker), but where there is a story to tell, what tools are choreographers using to get it across? Film is one, with projected titles, or the BalletBoyz showing short films before their pieces to give the viewer an in. Morgann Runacre-Temple and Jessica Wright used on-stage film very effectively in their acclaimed Coppélia for Scottish Ballet, highlighting details in closeup. More often, especially in contemporary dance, it’s through text. Akram Khan is a good example, using voiceover in his acclaimed solos Desh and Xenos to tackle ever more complex ideas. Crystal Pite has played with spoken and voiceover text, plus she even used shadow puppetry as an explainer when tackling Shakespeare in The Tempest Replica. DV8 founder Lloyd Newson shifted almost wholesale into theatre out of frustration about not being able to express complex ideas through dance.

Matthew Bourne, one of dance’s best current storytellers, thinks if you can’t do it in dance, you shouldn’t do it. “You need to have a passion to tell that particular story,” he says. “It shouldn’t just be an excuse to do a lot of nice steps and some great duets.” Whereas David Nixon, ex-artistic director of Northern Ballet, says: “I always think the story is the inspiration but really it’s about the dance. I feel the audience come to see the dancers in the vehicle of the choreography.” He also thinks if a ballet is based on an existing source, the audience should come with knowledge of it. “But maybe I’m old school.”

Bourne made his name taking stories people already know and giving them an unexpected twist – like his male-chorus Swan Lake, or Sleeping Beauty turned into a vampire tale, which he’s touring this winter. He never doles out a detailed synopsis. “I hate the idea of reading beforehand what’s going to happen at the end,” he says. “You’d hate that in a film.” He sits in the audience and watches people’s responses to see if they’re getting it. “Sometimes the thing you see in your head is not what everyone else is seeing.” He’ll keep tweaking the piece until everyone laughs in the right place. Sometimes people see things he never intended. “The classic one is that there’s some sort of incestuous relationship between the Prince and the Queen in Swan Lake, because they dance together. That never crossed my mind!”

Rambert’s latest show, a dance version of Peaky Blinders, is deliberately trying to appeal to a broad audience of non-dancegoers, so it comes framed with a voiceover by Benjamin Zephaniah’s character. It even introduces the characters by name at the beginning – something I could definitely have done with in a few shows over the years. Still, the show’s dramaturg, Kaite O’Reilly, doesn’t want things to be too obvious. “I don’t think people want to be spoonfed,” she says. “Like [Jerzy] Grotowski said, the montage exists in the eye of the audience.” In other words, whatever you see is valid. “We can create symbols and images, suggest tone and atmosphere, but I really believe that the audience is telling the story themselves.”

Bourne likes a bit of ambiguity: “Sometimes you can kill the poetry by putting it down in black and white.” He doesn’t use dramaturgs – “that’s part of the choreographer’s job” – but you’ll increasingly see them credited on dance productions. Uzma Hameed works as a dramaturg with Wayne McGregor among others. “Sometimes people talk about the role as being about clarity,” she says. “I slightly push against that. I think it’s about complexity.”

Hameed is working with McGregor on a “rendition” of Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam trilogy for National Ballet of Canada. Calling it an “adaptation” would give the wrong idea. “We don’t like to give the impression you’re going to get a blow by blow recounting of the story.” For her it’s about looking at the bigger picture, not what the plot is, but “trying to delve into what that feeling is when you’re reading it, bringing the world of the book to life”. On McGregor’s very successful Woolf Works, that meant moving between narrative and biography with the kind of formal experimentation Virginia Woolf herself employed.

With Atwood, says Hameed, the mode is often satirical and full of contemporary parallels – the MaddAddam trilogy is about a global pandemic. McGregor and Hameed are thinking about how to match “the way she smashes together fiction and nonfiction in her work”. It’s a big ask. “It all feels very hard, to be honest.” But for her it’s much more rewarding than rehashing a plot. “If you go and see a ballet that recreates a book you already know, all you do is come out congratulating yourself on the fact you followed the story.”

Dance’s real magic often comes from bypassing explanation and getting straight into (sometimes ungraspable) feelings. But such an enigmatic art can also leave you feeling shut out when you can’t get a handle on the choreographer’s intentions. “I’ve definitely seen a lot of shows where I feel I’m completely lost, in an annoying way,” says Seke Chimutengwende, whose own work is often improvisatory and experimental. His regular dramaturg, Charlie Ashwell, agrees they’ve been lost, too. “But I like that!” they laugh.

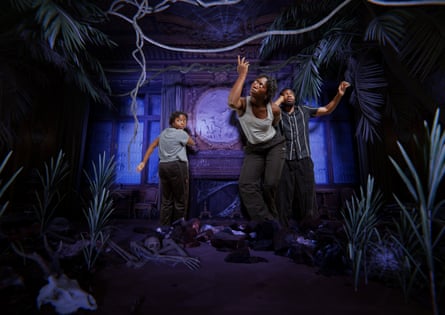

In non-narrative works, a dramaturg might help shape its “energetic structure”, says Chimutengwende, “playing with expectation and timing and intensity”. His latest piece, It Begins in Darkness, is about the legacy of slavery and colonialism. Rather than attempt explanation or story, it’s more about being haunted by history – it draws on horror films and ghost stories. “It’s exploring how we feel about certain issues, which is different for different people,” he says. “I wanted to create a space where people could sit with those feelings, without a narrative. It’s a processing space. I guess in that sense there’s nothing to understand, other than that’s what the space is for.”

As Hameed says, the scale of the challenge is the appeal. “On one level it feels impossible to deal with the themes of this piece through a dance show, but that’s what’s interesting about it for me,” says Chimutengwende. “The flipside of that is there’s something very immediate about watching dance, the kinaesthetic response and seeing the images in the piece.” Audiences will inevitably be influenced by their expectations in advance – Ashwell sees the text they might write in marketing material or on social media as “almost part of the choreography”.

So how much does it matter if we understand what’s happening on stage? Nixon would say to his audience: “Don’t worry, just watch.” Hameed is happy to give the audience “permission not to understand,” she says, before taking apart the idea of “understanding”. “We understand dance in our body, and in that wider space of sensing and feeling that you call the soul or the heart, and that is also how we encounter life. There’s a combination of sensations and stimuli, sometimes a pattern emerges and for a moment you get this sort of insight.” It’s the same “mysterious process of unfolding” that makes up our lives, she says. “And that’s how dance speaks to us.”

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby is at Troubadour Wembley Park, London, 12 October-6 November, and touring. It Begins in Darkness by Seke Chimutengwende is at Attenborough Centre for the Creative Arts, Brighton, 11-12 October, and touring. Matthew Bourne’s Sleeping Beauty is at Theatre Royal Plymouth, 12-19 November, and touring. MaddAddam is at Four Seasons Centre, Toronto, 23-30 November.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion