Is Cheese Good for You?

Cheddar, Gouda, Brie, Gorgonzola, Parmesan. There’s a tempting type for every taste, and recent research shows that all of them can be part of a healthy diet.

Cheese is rich and creamy, and it’s irresistible on a cracker, paired with a selection of fresh fruit, or sprinkled over a bowl of chili. There are many delicious reasons to love cheese, and Americans really do love it. The per capita consumption is 40 pounds a year, or a little over 1.5 ounces a day.

As much as we love cheese, though, we’re a little afraid of it. When people talk about their fondness for cheese, it’s often in a guilty, confessional way, like “Cheese is my weakness.”

But “cheese is packed with nutrients like protein, calcium, and phosphorus, and can serve a healthy purpose in the diet,” says Lisa Young, RD, an adjunct professor of nutrition at New York University. So if Stilton makes you swoon or you always want more Parm on your pasta, know this: Research shows that even full-fat cheese won’t necessarily make you gain weight or give you a heart attack. It seems that cheese doesn’t raise or reduce your risk for chronic diseases, such as heart disease and type 2 diabetes, and some studies show it might even be protective.

Why Cheese May Be Good for You

It’s easy to see why people might feel conflicted about cheese. For years, the U.S. Dietary Guidelines have said that eating low-fat dairy is best because whole-milk products, like full-fat cheese, have saturated fat, which can raise LDL (bad) cholesterol levels, a known risk for heart disease. Cheese has also been blamed for weight gain and digestive issues like bloating. It turns out, though, that cheese may have been misunderstood.

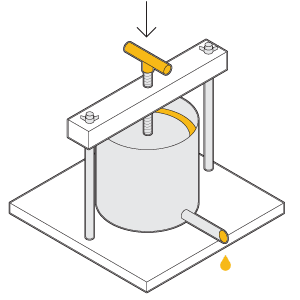

but they’re all made in the same basic way.

1. Cheese producers heat milk, usually from cows but also from goats, sheep, and even buffalo.

2. They add healthy bacteria–i.e., “cultures.” Different cheeses are made with different types of bacteria, which, in large part, are responsible for the flavor.

3. They add “rennet,” an enzyme that separates the curds (solids) from the whey (liquid).

4. Cutting the curds removes the whey. Small curds produce drier (harder) cheese, and large ones have more moisture.

5. The curds are usually salted. Then they’re stretched (e.g., fresh mozzarella) or poured into molds and pressed. Once removed from the molds, most cheeses are aged anywhere from a few weeks (like Brie) to several years (like Parmesan).

In 2018, Feeney led a six-week clinical trial in which 164 people each ate an equal amount of dairy fat either in the form of butter or cheese and then switched partway through the study. “We found that the saturated fat in cheese did not raise LDL cholesterol levels to the same degree as butter did,” she says.

Experts have varying theories about why the saturated fat in cheese is less harmful. “Some studies show that the mineral content in cheese, particularly calcium, may bind with fatty acids in the intestine and flush them out of the body,” Feeney says. Other studies suggest that fatty acids called sphingolipids in cheese may increase the activity of genes that help with the body’s breakdown of cholesterol.

When cheese is made it gains some beneficial compounds, too. “Vitamin K can form during the fermentation process,” says Sarah Booth, PhD, director of the Vitamin K Laboratory at the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University in Boston. The vitamin is important for blood clotting, and bone and blood vessel health. “Higher-fat cheeses, such as cheddar or blue, have the most.”

And as a fermented food, “both raw and pasteurized cheeses contain good bacteria that can be beneficial to human gut microbiota,” says Adam Brock, vice president of food safety, quality, and regulatory compliance for the Dairy Farmers of Wisconsin. (See “Is Raw-Milk Cheese Safe to Eat?”) This good bacteria, found mostly in aged cheeses such as cheddar and Gouda, help break down food, synthesize vitamins, prevent bacteria that cause illness from getting a foothold, and bolster immunity.

Your Body on Cheese

So cheese might not be a cholesterol worry, it offers important nutrients, and it can promote gut health. But wait, there’s more good news: Cheese seems to reduce the risk of weight gain (really) and several chronic diseases.

Weight gain: Cheese is a concentrated source of calories. “That’s why portions of cheese should be smaller compared to something like milk or yogurt,” says Young at New York University. Still, studies suggest that you don’t need to skip cheese to keep the scale steady. In one, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, researchers set out to determine which foods were linked to weight gain by following 120,877 men and women in the U.S. for 20 years, looking at their weight every four years. While they found that consuming more of certain foods, like refined grains (as in white bread), was associated with weight gain, eating more of others, like nuts, actually helped with weight loss. Cheese wasn’t associated with either gain or loss, even for people who increased the amount of it they ate during the study. Another review published in the journal Molecular Nutrition & Food Research in 2018 found that people who ate dairy, including cheese, weighed more than those who didn’t, but the dairy eaters had less body fat and more lean body mass, which is beneficial to health.

One reason cheese may help control weight is that it may reduce appetite more than other dairy products. In a small study, researchers measured appetite and the levels of four hormones that control hunger in the blood of 31 people after they ate cheese, sour cream, whipped cream, or butter. Among those foods, cheese caused a greater rise in two of the hormones that help you feel full.

Cardiovascular disease: A large meta-analysis of 15 studies published in the European Journal of Nutrition that looked at cheese’s impact on cardiovascular disease found that people eating the most (1.5 ounces per day) had a 10 percent lower risk than those who didn’t eat any. Other analyses have found that cheese doesn’t seem to affect heart disease risk either way. While many of these studies are observational, which means they don’t show cause and effect, together “the research suggests you don’t need to avoid cheese if you’re concerned about LDL cholesterol levels or heart disease,” Feeney says.

Diabetes and hypertension: Cheese and full-fat dairy also seem to be linked to a lower risk of both. In a study of more than 145,000 people in 21 countries, the researchers found that eating two servings of full-fat dairy or a mix of full-fat and low-fat was linked to a 24 and 11 percent reduced risk of both conditions compared with eating none. Eating only low-fat dairy slightly raised the risk. And among people who didn’t have diabetes or hypertension at the start of the nine-year study, those who ate two servings of dairy were less likely to develop the diseases during the study.

Lactose intolerance: Lactose, a sugar in milk, can be difficult for some people to digest, leading to diarrhea, bloating, and other gastrointestinal symptoms. But the bacteria used to make cheese digests most of the lactose in the milk, says Jamie Png of the American Cheese Society and a 12-year veteran of the cheese-making industry. Much of the lactose that remains is found in the whey, which gets separated from the curds toward the end of the cheese-making process and is drained off. “This means many types of cheese have very little to no lactose,” she says. “I’m a lactose-intolerant cheese maker, and my general rule is the higher in moisture a cheese is, the higher in lactose.” If you’re sensitive to lactose, stick to hard and/or aged cheese such as cheddar, provolone, Parmesan, blue, Camembert, and Gouda, and minimize fresh soft cheese like ricotta and cottage cheese. For instance, an ounce of cheddar has about 0.01 gram of lactose while a half-cup of cottage cheese has 3.2 grams. (A cup of whole milk has 12 grams.)

The Healthiest Way to Eat Cheese

If all this news has you ready to dig into a wheel of Brie with a spoon, hold up. Even though cheese itself doesn’t appear to have negative effects on health, how you incorporate it into your overall diet matters.

In much of the research suggesting a neutral or beneficial effect, the highest amount of cheese people ate was about 1.5 ounces, but in some cases it was up to 3 ounces. (An ounce of cheese is about the size of your outstretched thumb.)

In some studies, the health benefits of cheese were found to be the greatest when it replaced a less healthful food like red or processed meats. So there’s a big difference between crumbling some blue cheese over a salad and serving up a pepperoni pizza with double cheese. “Incorporating cheese into a Mediterranean-style diet where you also include fruits, veggies, whole grains, and other foods known to lower disease risk is going to be the most beneficial to your overall health,” Young says.

For those watching their sodium intake, cheese can be pretty salty. (The salt acts as a preservative.) If you’re eating about an ounce a day, it’s not a huge concern. Most types give you between 150 and 300 mg of sodium per ounce. (The daily value is no more than 2,300 mg.) Eat more, though, and the sodium can add up.

The form cheese takes may also influence how it affects health. “Many of the studies on cheese and health use cheese in a nonmelted form,” Feeney says. “We still don’t know how melting or cooking affects the health outcomes, for example, eating cheese on pizza or in cooked dishes like casseroles.”

Young suggests pairing cheese with fruit, nuts, or fresh vegetables like carrots and red peppers, and a few whole-grain crackers, or have it on a slice of whole-grain toast topped with tomato. When cheese has a starring role, you can focus on it and enjoy it more.

Fromage Facts

The nutrition content of cheese, including calories, fat, saturated fat, protein, calcium, and sodium, varies based on the type of milk used (cow, sheep, goat) and the process used to make it. Here’s what’s in some of your favorite cheeses, so you can choose the type that’s right for you.

The nutrition content is per 1-ounce serving. Note that the daily value (DV) for calcium is 1,300 mg; for sodium, it’s no more than 2,300 mg.

Brie

- Calories 95

- Fat 8 g

- Saturated fat 5 g

- Protein 6 g

- Calcium 52 mg (4% DV)

- Sodium: 178 mg (8% DV)

Cheddar

- Calories 113

- Fat 9 g

- Saturated fat 5 g

- Protein 6 g

- Calcium 199 mg (15% DV)

- Sodium 183 mg (8% DV)

Chèvre (Goat’s Milk)

- Calories 103

- Fat 8 g

- Saturated fat 6 g

- Protein 6 g

- Calcium 86 mg (7% DV)

- Sodium 118 mg (5% DV)

Cotija

- Calories 90

- Fat 6 g

- Saturated fat 4 g

- Protein 7 g

- Calcium 200 mg (15% DV)

- Sodium 480 mg (21% DV)

Feta (Sheep’s Milk)

- Calories 75

- Fat 6 g

- Saturated fat 4 g

- Protein 4 g

- Calcium 140 mg (11% DV)

- Sodium 323 mg (14% DV)

Gorgonzola

- Calories 100

- Fat 8 g

- Saturated fat 5 g

- Protein 6 g

- Calcium 150 mg (15% DV)

- Sodium 326 mg (14% DV)

Gouda

- Calories 101

- Fat 8 g

- Saturated fat 5 g

- Protein 7 g

- Calcium 198 mg (15% DV)

- Sodium 232 mg (10% DV)

Manchego (Sheep’s Milk)

- Calories 128

- Fat 10 g

- Saturated fat 7 g

- Protein 9 g

- Calcium 260 mg (20% DV)

- Sodium 120 mg (5% DV)

Mozzarella (Part Skim)

- Calories 84

- Fat 6 g

- Saturated fat 3 g

- Protein 7 g

- Calcium 198 mg (15% DV)

- Sodium 189 mg (8% DV)

Mozzarella (Fresh)

- Calories 70

- Fat 5 g

- Saturated fat 3.5 g

- Protein 5 g

- Calcium 60 mg (5% DV)

- Sodium 100 mg (5% DV)

Parmesan

- Calories 111

- Fat 7 g

- Saturated fat 4 g

- Protein 10 g

- Calcium 335 mg (25% DV)

- Sodium 335 mg (15% DV)

Queso Fresco

- Calories 85

- Fat 7 g

- Saturated fat 4 g

- Protein 5 g

- Calcium 160 mg (12% DV)

- Sodium 213 mg (9% DV)

Swiss

- Calories 111

- Fat 9 g

- Saturated fat 5 g

- Protein 8 g

- Calcium 252 mg (19% DV)

- Sodium 53 mg (2% DV)

Editor’s Note: This article also appeared in the November 2022 issue of Consumer Reports magazine.