Everlasting Lightbulbs? They Exist. Well, Existed

Nothing lasts forever, except, it seems, some lightbulbs.

Could we ever create a lightbulb that lasts forever? If we could, should we?

As you are about to find out, they have been created in the past, but they risked not proving beneficial for all concerned if they became widespread.

Let’s find out why.

Do light bulbs that last forever exist?

Given the amount of money you are likely to spend on replacing spent lightbulbs every year, you might be wondering if there are any that could, theoretically, last nearly forever. As it turns out, there actually is.

Called the Centennial Light, this is the world’s longest-lasting lightbulb. It is located at Firestastion No. 6, 4550 East Avenue, Livermore, in California. Operated by the Livermore-Pleasanton Fire Department, the bulb was first installed in 1901.

Incredibly, it has remained illuminated pretty much constantly ever since (with the exception of being moved several times throughout its history).

To date, the bulb has been running for well over a million hours — a feat that puts many of today’s “longlasting” bulbs to shame.

It was originally installed at the fire department’s Hose Cart House but was later moved to the main firehouse the same year. In 1903, it was moved again to Station 1, and later survived a renovation of the building in 1937.

For the first 75 years of its operation, the bulb was connected directly to the 110-volt city power system and was moved again, under police and fire truck escort, to its present location. The bulb is currently connected to its own independent 120V power source with a UPS (uninterruptible power supply). In 2013, the UPS actually failed, and the bulb was off for around 9.5 hours.

According to the bulb’s official website, when it was finally reconnected, the bulb shone at 60 watts for a few hours before dimming again to its “usual” 4 -watt condition. Why this happened remains a mystery.

Handblown, the bulb operates at low power, about 4-watts, and was designed to provide just enough nighttime illumination for crews to see. The “Centennial Bulb” is a type of improved incandescent bulb that was invented by Adolphe A. Chaillet and was made by the Shelby Electric Company. The bulb’s filament is made of carbon and has a maximum wattage of 60 watts.

The bulb was, according to historical records, originally donated to the fire station by Dennis Bernal of the Livermore Power and Light Company.

This is an incredible achievement, and one that has been officially recognized by the Guinness World Records. Interestingly, the bulb’s continuous illumination is likely the secret behind its longevity, as we’ll discuss in the next section.

At present, the Fire Department plans to allow it to run for as long as it can. If, and when, the bulb finally fails, there are plans to display the bulb in a specially designed museum with other fire fighting equipment.

Visits to the bulb are available on request and/or availability of fire crew at the station. Other than that, visitors can view the bulb through an external window.

Why do incandescent bulbs burn out?

As impressive as the record for the “Centennial Bulb” is, you will know from experience that typical incandescent bulbs have a much shorter lifespan. Typically (depending on use), incandescent bulbs will last for about 2,000 hours — that’s usually less than a year if turned on 6-hours a day.

But why does this happen?

The main reason is that the filament in regular bulbs is made of tungsten rather than carbon, as in the “Centennial Bulb”. When operational, this filament burns white-hot in order to give off visible light.

In fact, only about 5% of the electricity used in such bulbs is converted to light. The rest is “wasted” as heat. In essence, incandescent lightbulbs can be described as heated lamps that give off a little bit of light as a byproduct. This is one of the main reasons that incandescent bulbs are an important factor when calculating the required heating and cooling costs of a building, and why they are being phased out in many countries.

But we digress.

On the atomic level, the excessive heat involved in keeping these bulbs illuminated results in tungsten atoms changing from solid-state to gaseous vapor over time. This causes the filament to thin as mass is removed from it.

Not only that, but this thinning is not uniform over the filament, with some parts thinning at different rates to others. It is these thinner spots that will later prove fatal to the bulb.

In vacuum bulbs, the free tungsten atoms collect on the inside of the glass, and the glass starts to get darker. Many modern light bulbs, however, use inert gases, such as argon, to reduce this loss of tungsten. When tungsten atoms evaporate, they collide with an argon atom and bounce back, rejoining the filament.

When the bulb is active, the current running through it is equal, but the filament thickness is not. This causes the thinner parts to burn hotter, and hotter, accelerating the evaporation of tungsten over time.

The problem is also compounded by the act of turning the bulb on and off continuously.

Every time this happens, the filament cools, and shrinks, creating microscopic cracks in the filament — further compounding the problems described above. Called thermal cycling, the constant thermal expansion and contraction of the filament reduce the lifespan of the bulb significantly.

This is partly due to the reduced electrical resistance of the metal when cold, which allows more current to pass through it than once the metal has heated up. This process usually takes milliseconds.

When you think about it, it is small miracle that these bulbs do not burn out sooner. The small filament of tungsten must resist a change in temperature from room temperature to around 3,000 degrees Celsius (5,432 degrees Fahrenheit) in less than a few thousandths of a second!

That is very hot, to put it mildly. In fact temperatures like this are about half that of the surface of the sun.

At these kinds of temperatures, most materials will either melt or burn. It is for this reason, that one of the developers of the modern lightbulb, Warren De la Rue, came up with the bright idea (pun intended) of enclosing the filament (which was platinum in his bulb) in a vacuum, removing most of the oxygen so there would be fewer gas molecules to interact with the platinum, making it last longer.

This is usually not a problem for new or well-made bulbs, but as the filament weakens over time, there will come the inevitable moment when this surge proves too much for the filament and it breaks.

The “Centennial Bulb,” on the other hand, has a filament made of carbon, which is far stronger than tungsten, as it runs continuously at a much lower wattage than your average incandescent bulb. This combination of stronger material, and the constant supply of electrical current, all help to keep the bulb “alive” for as long as it has.

What are the world’s other longest-lasting light bulbs?

Apart from the “Centennial Bulb,” there are few other exceptionally long-lasting bulbs too.

One example, widely credited as the world’s second-longest-running bulb, can be found at Fort Worth in Texas. Known as the “Eternal Light,” this bulb was originally recognized as the world’s longest-lasting bulb until the discovery of the “Centennial Bulb” a few years later.

First turned on in 1908, this bulb has been in more-or-less continuous operation ever since.

Other examples include another bulb located above the back door of Gasnick’s Supply store in New York City. It was first installed in 1921, according to the store’s owner, and its current location, and condition, are not currently known. However, there was considerable doubt as to the claims of the store’s owner at the time.

The store, and the block in which the store was located, have since been demolished.

What is the world’s oldest light bulb?

The aforementioned “Centennial Bulb” is, as far as we know, the world’s longest-running bulb, but it might not be the oldest. Another, called the “Ediswan Light Bulb” might be even older.

Allegedly first turned on 1883, this bulb might just be the world’s oldest surviving light bulb. Located in Heysham, England, the bulb is owned by Beth Crook, who claims that the bulb was first owned by her ancestor Florence Crook and has been passed down through the family over the years.

Unlike the “Centennial Bulb,” this light bulb has only been used sparingly throughout its life, artificially extending the bulb’s lifespan.

It was first manufactured by the Ediswan factory and was the product of a collaboration between the British lightbulb creator Joseph Swan and Thomas Edison. This collaboration, or rather merger, was the result of a lawsuit between Edison’s company and Swan’s that resulted in the two merging in the UK in 1883.

However, this merger proved to be a storming success, as other companies in the UK were unable to compete. Their “Ediswan” bulbs, produced in the company’s factories in Sunderland, Brimstown, and Ponders End would dominate the market for many years.

Why are no everlasting bulbs commonly available today?

As we have seen, there are quite a few examples of bulbs that are still going strong after well over 100 years of operation. So, since the technology obviously exists, you might be wondering why none are commonly available for use today?

The answer put simply, is an example of something a true conspiracy and an example of business practice called planned obsolescence.

Planned obsolescence is a business strategy that ensures the current version of a product will become outdated, or even useless, within a set time period. The idea is that such a built-in limitation will ensure that consumers will seek replacements in the future — therefore boosting sales.

You can see it in many products today, like smartphones, but also in less obvious things like lightbulbs.

But, it wasn’t always this way. Back in the days when lightbulbs were cutting-edge technology, various inventors were working hard to make them last as long as possible. Warren De la Rue, as we previously mentioned, made something of a leap in this area by enclosing the filament in a vacuum bulb.

Later inventors, including Thomas Edison, would later experiment with different filaments, like cotton, platinum, or even bamboo, to attempt to extend the life of bulbs. A very good balance was found with tungsten which, while not the best, when combined with inert gas, offered an acceptable lifespan when balanced with manufacturing costs.

By around the 1920s, most bulbs had lifespans approaching 2,000 hours (like today) with some pushing 2,500 — apart from the exceptional examples discussed earlier.

Things were looking up.

But this all changed around 1924 when lightbulb manufacturers held a secret meeting in Geneva 1924. The likes of Philips, International General Electric, OSRAM, and others, all decided to form a group called the “Pheobus Cartel“. Pheobus, in case you are not aware, was the Greek god of light.

The main objective of this cartel was to agree to control the supply of light bulbs. Each understood that if any one of them managed to develop a long-lasting light bulb, the need for replacement bulbs would likely dry up.

Bulbs were lasting too long. Not ideal from their point of view.

So, to combat this, all members of the cartel agreed to reduce the lifespan of bulbs on purpose. Initially, this was set to no more than 1,000 hours!

To enforce this, and prevent any one of them from breaking the agreement, samples of bulbs needed to be sent to a central authority that would test them for longevity.

The manufacturer of any bulbs that lasted longer than the set minimum would be fined. These fines could be considerable, with a fine of 200 Swiss francs for every 1,000 bulbs sold (if the bulb lasted more than 3,000 hours).

To ensure this wouldn’t happen, engineers previously tasked with extending the lives of bulbs were suddenly tasked with doing the exact opposite. Different filaments, filament designs, and connections were tested over time and by the mid-1920s most lightbulbs lasted, on average, about 1,200 hours apiece.

As planned, sales increased. Not only that but savings made in cheaper components were not translated to the consumers — prices remained relatively stable.

So why, you might ask, didn’t consumers complain? The simple answer is that they didn’t know. The cartel was officially established to provide standardization and efficiency of bulbs.

For example, they successfully developed the now ubiquitous screw thread still seen today. The cartel was initially planned to continue until the 1950s, but non-compliance among members and the outbreak of WW2 saw it ended by the early-1940s.

What are some examples of planned obsolescence today?

Despite its demise, the Pheobus Cartel had set a precedent that many companies still use today. One of the most famous examples was Apple with its iPod.

These devices would notoriously suffer from battery issues within the first 2 years of purchase. Customers who wanted to extend the life of the product would be charged a large refurbishment fee, often just shy of the regular retail price of a new unit.

For obvious reasons, many customers would rather just buy and new one than get their old ones fixed. This eventually led to a class-action suit against the company, which was settled out of court.

However, it is a practice that companies like Apple continued to carry out — especially with their iPhones. In 2020, Apple agreed to pay $113 million to settle consumer fraud lawsuits brought by more than 30 U.S. states over allegations that it secretly slowed down old iPhones, in a controversy sometimes referred to as “batterygate.”

Apple claimed that the update had throttled the battery on older devices to extend their lifespans. This would not really be an issue if the battery could be replaced easily — which it couldn’t with iPhones.

What are the pros and cons of planned obsolescence, if any?

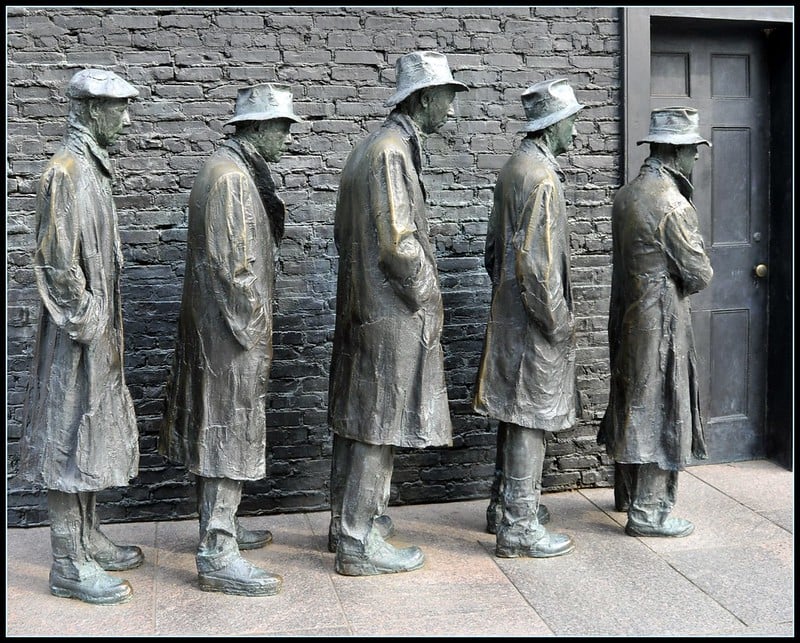

While planned obsolescence might sound like a devious and unethical practice, some have argued that there might be some legitimate upsides to it too. During the Great Depression, for example, millions of people in the U.S. and around the world were made redundant.

At that time, mandatory obsolescence of products was seriously considered to provide a pipeline for getting people back to work. It was proposed by American real estate broker Bernand London, who argued that such a practice would be good for everyone.

He suggested that the government impose a “lease of life” on things like shoes, homes, even machines to help generate jobs. After a set limit, the government would collect and destroy these products during times of widespread unemployment.

Rather than the methods employed by the likes of Apple, consumers would be well aware of the “lifespan” of products they bought.

While this might sound like a crazy idea, there is some logic to it. Consider for a moment if products could be made that never failed.

Once made, these products could last forever and never need repairs. Eventually, everyone would have one and the need for new units would eventually end.

This would not only impact the manufacturer’s bottom line, and even their need to stay in business, but could also conceivably impact other businesses who might rely on third-party services like cleaning or repairs of such products for an income.

Another potential benefit of planned obsolescence, it could be argued, is the freeing up of scarce resources “locked” up inside old things like tech. Take rare earth metals, for example.

Lithium, nickel, cobalt, and even precious metals like gold and silver, are regularly “consumed” when pieces of technology are built. So long as these materials are “locked” within older devices, raw minerals need to be extracted, refined, and shipped.

The processing of these materials can be very harmful to the environment, as we explored in a recent article on a similar subject.

As tech is a notoriously fast-developing field, the continuing use of older, slower, and less capable technology effectively prevents these precious resources from being available for new and improved devices. Under such circumstances, it could be argued that building a time limit on such devices could be beneficial to the environment — especially if the materials in the older devices could be recycled to create the new devices.

But, we’ll let you decide on whether this is a true benefit or not.

“Planned” or inherent obsolescence?

It is important to note that not all and manufacturers purposefully make their products last less time than they could. Some products, like tires for example, have a realistic maximum lifespan that cannot realistically be extended.

Tires are designed to provide friction, and, as such, will wear out over time. While there are ways to make them more durable — the use of harder rubber, for example — will likely reduce their grip — not ideal.

Other products are only as useful as their physical constraints as well. Take a DVD. These can only hold so much data, as they have a limited size. Is this planned obsolescence?

Yet other products inherently become obsolete over time as newer emerging technologies superseded them too. For example, Cloud storage and apps are replacing DVDs, washing machines have replaced the traditional wringer, barely anyone has a black and white TV today, older computers may struggle to connect to the internet or to run modern programs and apps.

Computer software is another important example, especially with regard to software updates. Eventually, the updates will stop working on older models, or will stop being released for older models, or they will take up so much memory that the device will slow down. Improvements to hardware also drive the development of software (and vice versa), quickly making either obsolete — is this really “planned”?

The list goes on.

What can be done about planned obsolescence?

So, with planned obsolescence fairly widespread in many industries, is there anything that consumers can do to fight back?

Well, one area that this practice is finding resistance is in the form of government legislation. Various states in the U.S., as well as member states of the EU, are toying with a “right to repair” to force manufacturers to make it easier for their customers to fix older products without voiding their warranties or using third-party providers.

Some in the private sector are also becoming more mindful of the need to make their products more future-proof. Modular cellphones, like the Fairphone are designed from the ground up for easy repair and upgrade after their initial purchase.

For PC users, the ability to swap out obsolete parts is nothing new, but for laptop users, the ability to upgrade just certain components has always been a little frustrating. This is where the likes of the “Framework” laptop may prove to be a gamechanger in the market.

These kinds of initiatives are likely music to the ears of many who have become frustrated with their latest tech lasting a few short years.

But, there is another weapon in the arsenal of companies to “trick” you into trading in your old products for new ones — psychology.

Through various tactics like changing the color, to marginal design changes, or incremental technological improvements, some companies have become masters of something called “dynamic obsolescence.”

This concept is rife in the world of fashion, with clothing lines generally lasting just one “season” before the clothing is deemed to be “out of style”. But this is not isolated to clothing, tech companies do the same thing.

Slightly larger screens, rounded or squared corners, a few more cameras on the back, or some fancy new built-in features, are all ways to make you buy what is essentially the same product from last year, but “better.”

But, there is some light at the end of the tunnel. Since we started on the subject of lightbulbs, it would be appropriate to end on them as well.

This is one area where we may have come full circle with regards to the planned obsolescence of products. Newer, more energy-efficiency bulbs like CFLs, and LEDs are now commonplace. These last much longer than their incandescent predecessors, with some LED bulbs lasting anywhere between 10 and 50 times longer than an equivalent traditional bulb.

With LED lightbulbs lasting, on average, between 10,00 and 50,000 hours (roughly ten years for normal domestic use), these are effectively everlasting. Now, we just need to make everything else as durable.

No pressure.

SHOW COMMENT ()

SHOW COMMENT ()